How the female form ended up perpetuating misogyny in the motoring industry.

Driven Women Magazine, Issue Five 2020 (PDF)

A long and thin neck, rounded shoulders and curvaceous hip line like that of a Renaissance Venus; the Coca-Cola bottle has, for many years, been a representation of the American dream. It’s appeared in art as a motif for capitalism, consumerism and carnal pleasures, most notably in the works of Salvador Dali, Robert Rauschenberg, Ai Weiwei and of course, Andy Warhol, whose description of his love for Cola, “Pop”, inspired the name of an entire art movement dedicated to fast, modern industry.

It’s a little-known fact that the original bottle, by Swedish engineer Alex Samuelson in 1915, was not actually designed

to stir sensual desire. Instead, it was inspired by the shape of the kola nut. However, by the era of Post-War America, a time where sex sold, it had fizzed its way toward being associated with unadulterated hedonism. The truth behind the shape

no longer mattered and the Coke bottle simmered with feminine sexuality. It became a Kim Kardashian-like icon that has for decades, appeared as a motif for freedom, happiness, capitalism, sexuality and industrial design – and continues to today. Why are we talking about Coca-Cola? Because, for all the things it personifies, it is a mass-made consumer product transformed into a myth. A move from a playbook that has been used one other thing: the automobile.

Since the Post-War era, the car has been marketed as an embodiment of all the things mentioned above, but perhaps most overtly, sex. Before the late 1950s, the most desirable shape in a mass-made car was that boxy, flat-lined, boat-like design. But soon, it was to give way (particularly during the Detroit boom) to a more curvaceous, silhouette, marketed as power-enhancing. Internal combustion engines, with pistons and oil and chambers and rhythmic mechanical movements have long been used as a metaphor for sex. Just as car design has been linked to the shape of a woman.

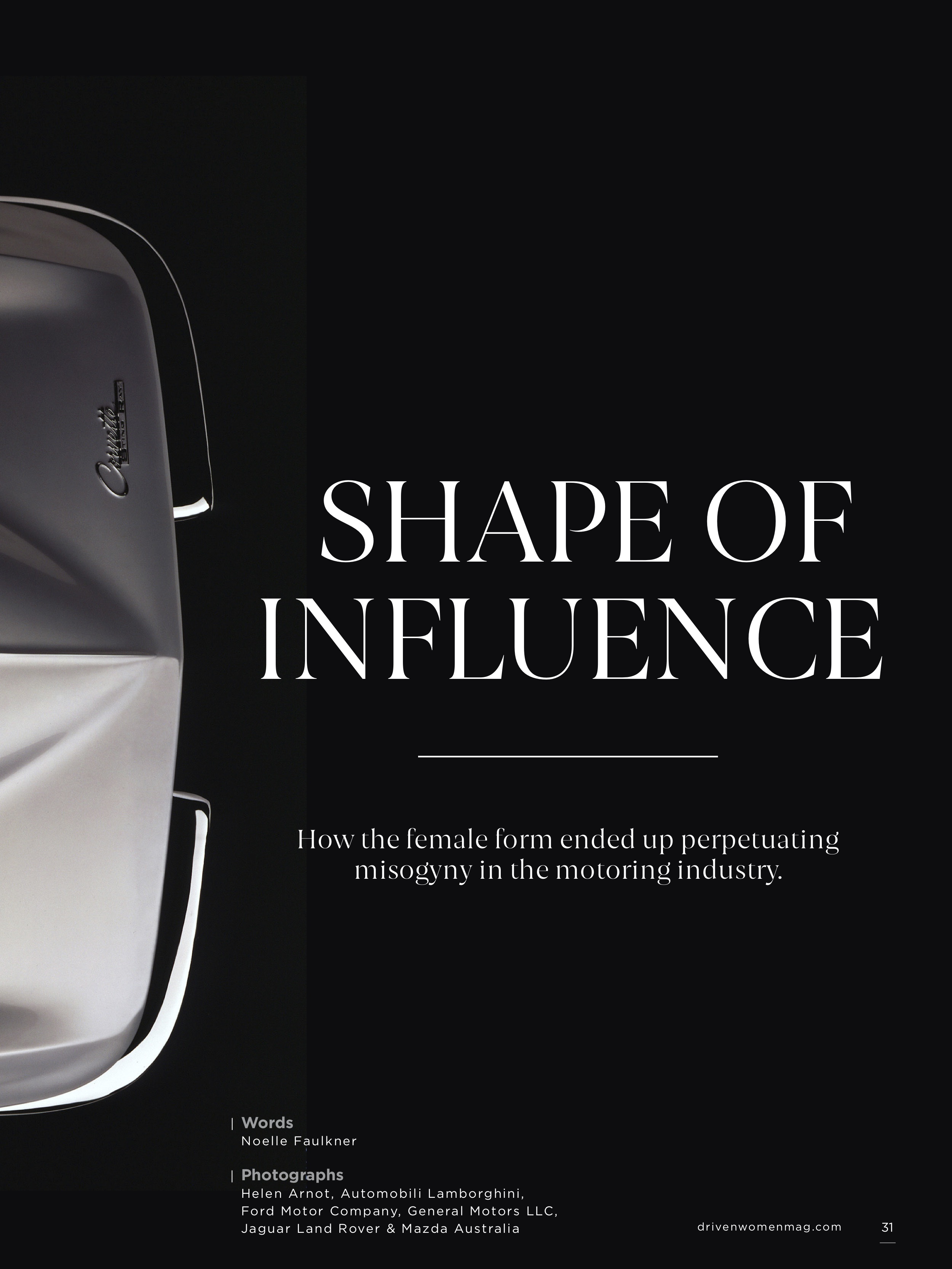

Take the high hipbones of the C2 Corvette Stingray or the phallic, bulbous silhouette and front-end air intake of the Jaguar 'E Type', for example; two cars that do not hide their shameless sexual suggestiveness and sold in great numbers because of it. Brands like Ferrari with the 250 Testa Rossa and the softness of the Roma; Alfa Romeo with the Type 33 Stradale and TZ1; and Porsche with the 911’s timeless shape that still endures today (not to mention its cheeky vintage advertising campaigns), have banked on the sly wink of lust as well.

Hilariously though, Ford's biggest flop, the Edsel of 1957, had a vertical, deep, front grille that was its undoing. It seems that while men were happy to sexualise the perfect curves and fleshy cockpits of their cars, an actual depiction of a vulva was taking it too far.

Beyond callipygean curves and phallic gear shifters, the quasi- erotic relationship of a “man” and his car ultimately lies in ideas of control. It’s this intention that drives so much misogyny within the automotive industry. Like the vagina Ford, it’s not without irony - while women have not been welcome, they have always been the centre rod of automotive in some way.

At the pop-cultural peak of the car, it was a constant emblem of status and place. Where it was a symbol of power and autonomy for James Bond, it was a rearview mirror which was often used to depict a woman re-applying her red lipstick, or the prop a Hollywood Bombshell would drape herself over.

Women were used to sell cars and in the very small amount of times advertisements targeted women themselves, it was in a highly submissive, patronising and misogynistic tone. Golden- era marketing sold cars as women, possessions a man can own, control and take care of. Metaphors of a car being an exotic woman, a temptress, a flirtation and a possession that can at once frustrate and excite has been a trope that has spanned many artforms – the “trade up to a younger model” joke? Where do you think that was derived from? Most common were the play on gender roles that played a huge part in how a car was perceived by consumers and manufacturers alike: Family cars were marketed as a must- have item to take care of women and children, while sports cars and convertibles were, simply, a way to conquer us.

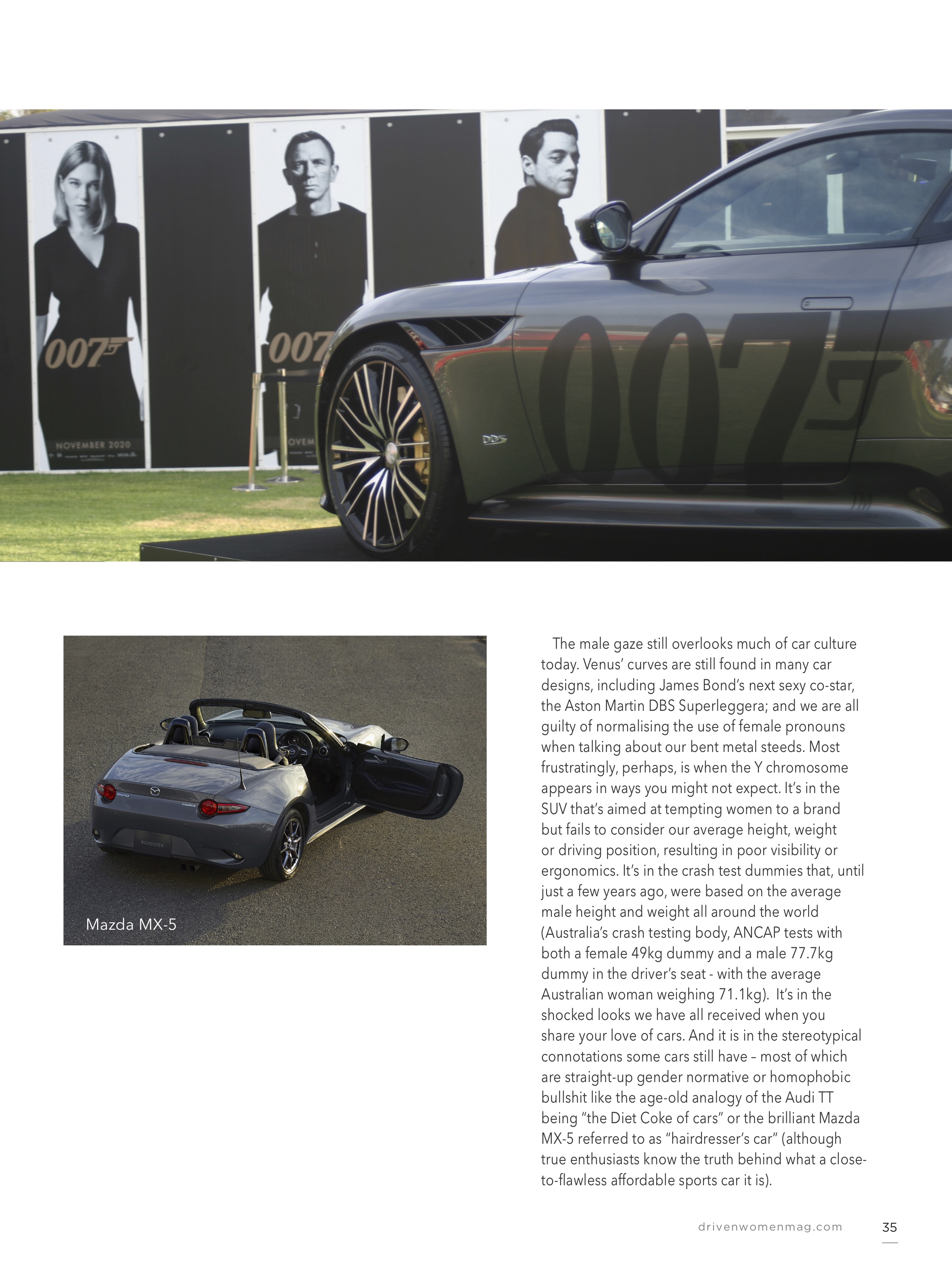

The male gaze still overlooks much of car culture today. Venus’ curves are still found in many car designs, including James Bond’s next sexy co-star, the Aston Martin DBS Superleggera; and we are all guilty of normalising the use of female pronouns when talking about our bent metal steeds. Most frustratingly, perhaps, is when the Y chromosome appears in ways you might not expect. It’s in the SUV that’s aimed at tempting women to a brand but fails to consider our average height, weight or driving position, resulting in poor visibility or ergonomics. It’s in the crash test dummies that, until just a few years ago, were based on the average male height and weight all around the world (Australia’s crash testing body, ANCAP tests with both a female 49kg dummy and a male 77.7kg dummy in the driver’s seat - with the average Australian woman weighing 71.1kg). It’s in the shocked looks we have all received when you share your love of cars. And it is in the stereotypical connotations some cars still have – most of which are straight-up gender normative or homophobic bullshit like the age-old analogy of the Audi TT being “the Diet Coke of cars” or the brilliant Mazda MX-5 referred to as “hairdresser’s car” (although true enthusiasts know the truth behind what a close- to-flawless affordable sports car it is).

In 2020, women are still shaping the automotive industry and we're reclaiming those power symbols and suggested sexual prowess as our own. As manufacturers realise women play a leading role in up to 85 per cent of car purchases, that we won't be talked down to and that we have also never been as financially independent as we are today, the golden era of motoring misogyny begins to fade, just like the fizz of an open Coke bottle. Women have always been at the heart of the automobile, be that as a muse, message, desire, owner or object, and we still cause ripples across design, business, education, sales strategy and car culture directly. Here’s to self-possession and driving ourselves.