GQ Australia, November/December 2020 (LINK) (PDF)

With a promising move to a new team on the horizon, Aussie F1 star Daniel Ricciardo is on the edge of glory. But as hungry as he is to win, racing isn’t everything.

Let’s finish what we started.” Daniel Ricciardo calmly pressed his team, determined, hungry. It’s September’s Tuscan GP at Mugello Circuit and for the entire race, the Perth-born Formula 1 racer had been driving flawlessly. 2020’s disruptions had meant several new tracks were added to the calendar, some of which had never hosted a Grand Prix before – this circuit included.

Among all the action – including two spectacular multi-car crashes within minutes, a pair of red flags, total restarts and only 12 out of 20 cars left in the race – was Ricciardo, the sport’s smiling assassin and one of only four Australians ever to win a race in Formula 1. In third position, Ricciardo had been pulling all his signature tricks out of the bag: swift, aggressive decisions; overtaking manoeuvres with effortless panache. He was primed for his first podium with Renault since he joined the team in 2019.

2020 had seen some chaotic races, but the Tuscan GP was one of the most intense in recent history. As Ricciardo tells it, “I drove the absolute wheels off the thing!” For everyone watching, it was a burning reminder that the 31-year-old is undoubtedly one of the finest drivers in Formula 1 today. Despite all his efforts, his Renault didn’t have enough guts against Alex Albon’s Red Bull, and after putting up a fight with just eight laps to go, Ricciardo crossed the line in fourth. The race was a tease for Ricciardo and his global fans; a droplet of water offered for an unquenchable thirst.

Situations like this have plagued the Monaco-based athlete of late, but as they say, ‘that’s racing’. Drivers, as good as they might be, can still be left to the mercy of their machines. This insatiable appetite, mixed with danger, physics, engineering and speed, is what has always made racing such an addictive, sexy sport. “Last week, everyone was like, ‘You’re so close to a podium! It’s gonna happen,’” Riccardo says when GQ meets him in London. “And I was like, ‘You know what? The truth is, I’ve won races, I’ve had podiums. So if I get another podium, it’s not like I haven’t done it already.’” As of the day we meet, Ricciardo has seven wins and 29 podiums under his belt. And as hungry as he is for more, again, ‘that’s racing’.

“It’s not the be-all and end-all,” he shrugs. “I left Sunday night very fulfilled. I had a lot of nice messages. I was happy, my parents were happy. They enjoyed the race. And I’ve made a lot of other people proud of me.” It’s this fine balance of focus, determination and genuine optimism that has seen Ricciardo propelled into the top flight, feet-first.

Ricciardo’s racing origin story starts a long way from Tuscany, at his family home in Perth. His father, Joe, had chased a dream of motorsport himself and would take to the racetrack for fun, family in tow. “Dad was always passionate about it,” he recalls. “Some weekends, I would be at a racetrack in my mum’s arms watching him, so from a very young age, I was exposed to the speed, sound and the smell.” As a child, Ricciardo was a typical Australian kid. He loved playing backyard cricket, soccer and tennis; just being outside. Karting, he says, was never forced on him – but there was something about the sport he couldn’t shake. “I was fascinated with speed,” he says, recalling his first time on the track. “Dad took me to an indoor karting place and I still remember driving down the little straight. The first thing I thought was just, ‘This is freedom.’ At seven or eight years old, I was in total control: ‘No one can touch me. I am literally free right now,’” he beams that million-watt smile. “I was in love with that.”

Eventually, Ricciardo’s parents, stretched from shuffling him from field to court to circuit gave him a choice. Ricciardo wanted to race. The decision wasn’t without hesitation – rental karts (and eventually, race cars), fuel and tyres are a lot more expensive than a pair of soccer boots. And besides, the odds weren’t exactly in his favour. No one from Western Australia had ever made it to Formula 1 before. He laughs, shaking his head, “I was winning some races, but was never the child everyone pointed at and said, ‘This kid’s going to F1!’ So, yeah, it took a bit of convincing.”

Unlike his European opponents, who seemingly learned to steer before they could walk, Ricciardo was a late-bloomer in the sport. In his final years of school, disinterested in academia, his appetite for racing flourished. Entering professional single-seater, open-wheel categories like Australian Formula Ford and Formula BMW Asia, his potential raised eyebrows.“I was quite immature at school,” he says. “I got to 17, and something just clicked – I fully committed to it.” That year, he moved to Europe to compete in various racing categories and his trajectory to Formula 1 started to gain traction.

The grounded, positive, cookie-cutter larrikin attitude that has made Ricciardo a star on and off the grid (and one of the reasons Optus has tapped him as a brand ambassador), has a lot to do with his early days in the sport. Europe wasn’t a luxury, it was a sacrifice. Ricciardo deeply loved and missed Australia (and still does), and was plagued with that imposter syndrome Australians know all too well. “I hadn’t convinced myself that I was good enough,” he says. “I was like, ‘Well, if I can’t dominate in Australia, how am I going to be able to dominate in Europe where the sport is 10 times as big and 10 times as competitive?’”

The moment was pivotal. “I became crazy disciplined,” he says. “You’d think living alone in Italy at 17, 18 – you can drink and party, but I didn’t. I was determined to make it happen.” He adds, “I watched other young drivers completely take advantage of the situation. They were like, ‘Well I’m a race-car driver, and I’m living in Europe and I’ve made it.’ But we couldn’t be further away from making it.” The naturally competitive Australian noted his competitors’ mistakes. “I could see the path they were on. But my parents had invested money and family friends had helped out, financially, for me to be able to do this. My dad worked too hard to make his money for me to piss it away.”

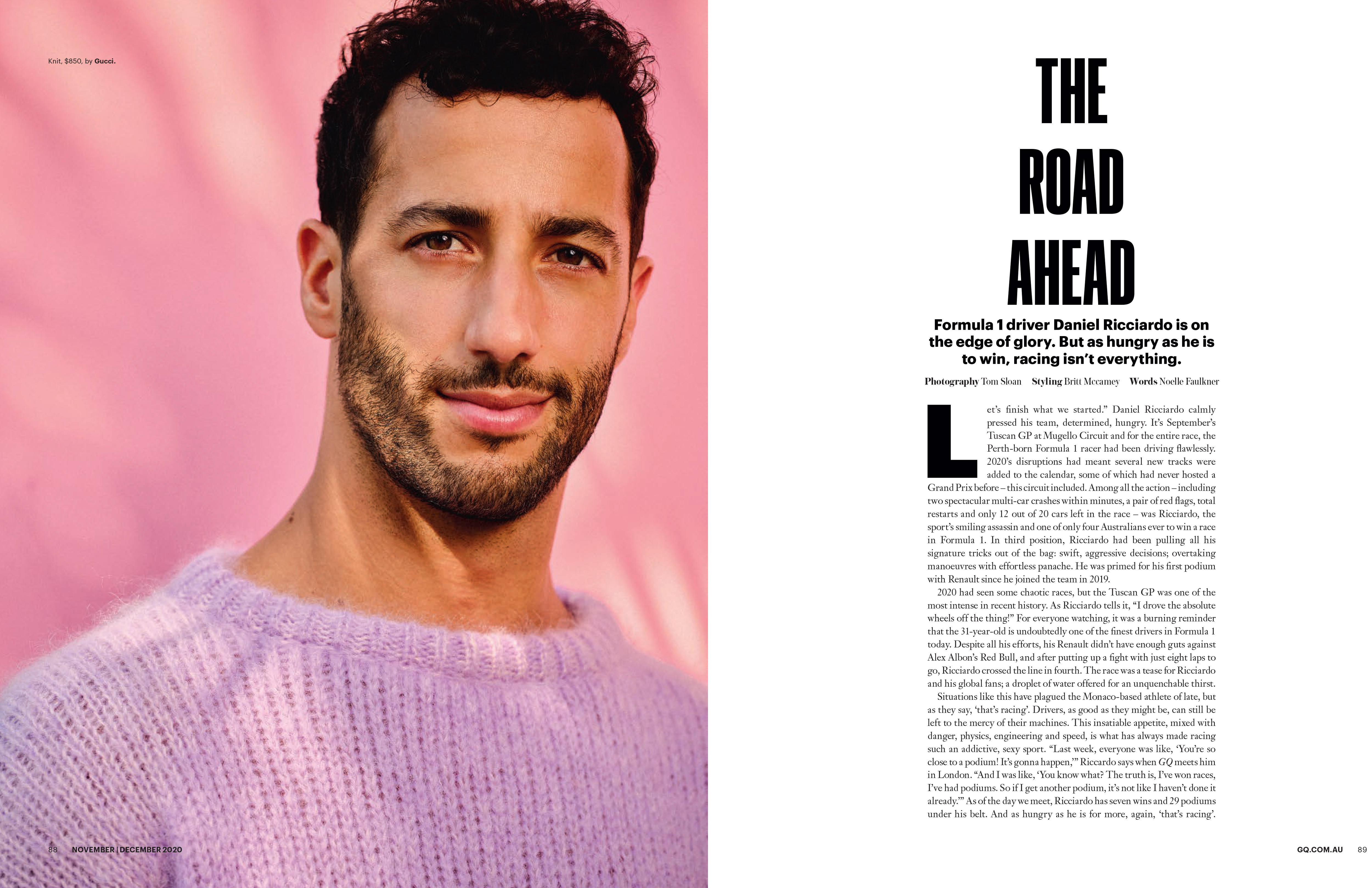

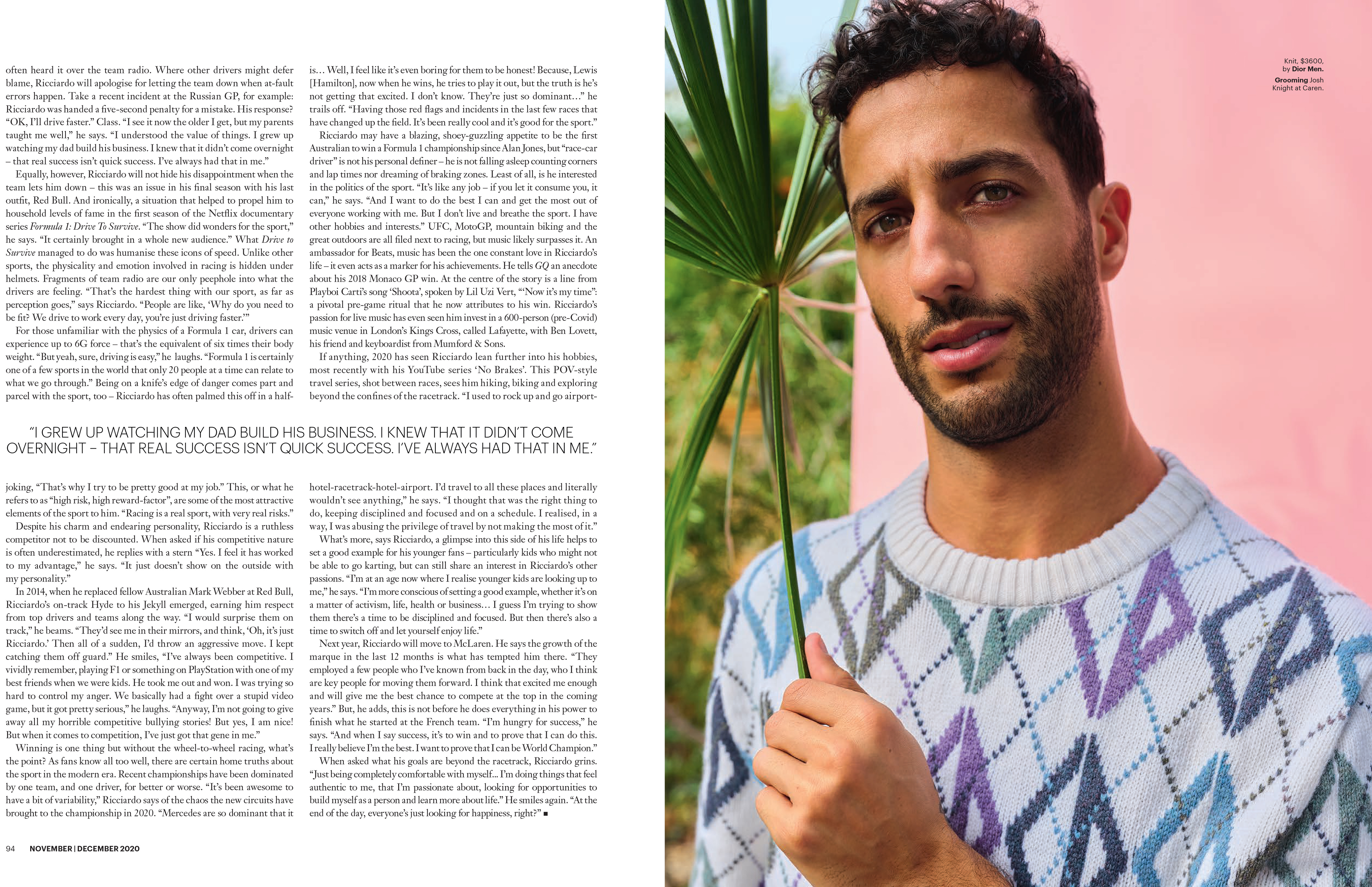

One of the most frequently complimented professional traits Ricciardo possesses is his upbeat sense of duty to his team, sponsors and family. We see this in London on the set of our GQ cover shoot and have often heard it over the team radio. Where other drivers might defer blame, Ricciardo will apologise for letting the team down when at-fault errors happen. Take a recent incident at the Russian GP, for example: Ricciardo was handed a five-second penalty for a mistake. His response? “OK, I’ll drive faster.” Class.

“I see it now the older I get, but my parents taught me well,” he says. “I understood the value of things. I grew up watching my dad build his business. I knew that it didn’t come overnight – that real success isn’t quick success. I’ve always had that in me.” Equally, however, Ricciardo will not hide his disappointment when the team lets him down – this was an issue in his final season with his last outfit, Red Bull. And ironically, a situation that helped to propel him to household levels of fame in the first season of the Netflix documentary series Formula 1: Drive To Survive.

“The show did wonders for the sport,” he says. “It certainly brought in a whole new audience.” What Drive to Survive managed to do was humanise these icons of speed. Unlike other sports, the physicality and emotion involved in racing is hidden under helmets. Fragments of team radio are our only peephole into what the drivers are feeling. “That’s the hardest thing with our sport, as far as perception goes,” says Ricciardo. “People are like, ‘Why do you need to be fit? We drive to work every day, you’re just driving faster. For those unfamiliar with the physics of a Formula 1 car, drivers can experience up to 6G force – that’s the equivalent of six times their body weight.

“But yeah, sure, driving is easy,” he laughs. “Formula 1 is certainly one of a few sports in the world that only 20 people at a time can relate to what we go through.” Being on a knife’s edge of danger comes part and parcel with the sport, too – Ricciardo has often palmed this off in a half-joking, “That’s why I try to be pretty good at my job.” This, or what he refers to as “high risk, high reward-factor”, are some of the most attractive elements of the sport to him. “Racing is a real sport, with very real risks.” Despite his charm and endearing personality, Ricciardo is a ruthless competitor not to be discounted.

When asked if his competitive nature is often underestimated, he replies with a stern “Yes. I feel it has worked to my advantage,” he says. “It just doesn’t show on the outside with my personality.”

In 2014, when he replaced fellow Australian Mark Webber at Red Bull, Ricciardo’s on-track Hyde to his Jekyll emerged, earning him respect from top drivers and teams along the way. “I would surprise them on track,” he beams. “They’d see me in their mirrors, and think, ‘Oh, it’s just Ricciardo.’ Then all of a sudden, I’d throw an aggressive move. I kept catching them off guard.” He smiles, “I’ve always been competitive. I vividly remember, playing F1 or something on PlayStation with one of my best friends when we were kids. He took me out and won. I was trying so hard to control my anger. We basically had a fight over a stupid video game, but it got pretty serious,” he laughs. “Anyway, I’m not going to give away all my horrible competitive bullying stories! But yes, I am nice! But when it comes to competition, I’ve just got that gene in me.”

Winning is one thing but without the wheel-to-wheel racing, what’s the point? As fans know all too well, there are certain home truths about the sport in the modern era. Recent championships have been dominated by one team, and one driver, for better or worse. “It’s been awesome to have a bit of variability,” Ricciardo says of the chaos the new circuits have brought to the championship in 2020.

“Mercedes are so dominant that it is… Well, I feel like it’s even boring for them to be honest! Because, Lewis [Hamilton], now when he wins, he tries to play it out, but the truth is he’s not getting that excited. I don’t know. They’re just so dominant…” he trails off. “Having those red flags and incidents in the last few races that have changed up the field. It’s been really cool and it’s good for the sport.” Ricciardo may have a blazing, shoey-guzzling appetite to be the first Australian to win a Formula 1 championship since Alan Jones, but “race-car driver” is not his personal definer – he is not falling asleep counting corners and lap times nor dreaming of braking zones. Least of all, is he interested in the politics of the sport.

“It’s like any job – if you let it consume you, it can,” he says. “And I want to do the best I can and get the most out of everyone working with me. But I don’t live and breathe the sport. I have other hobbies and interests.” UFC, MotoGP, mountain biking and the great outdoors are all filed next to racing, but music likely surpasses it. An ambassador for Beats, music has been the one constant love in Ricciardo’s life – it even acts as a marker for his achievements. He tells GQ an anecdote about his 2018 Monaco GP win. At the centre of the story is a line from Playboi Carti’s song ‘Shoota’, spoken by Lil Uzi Vert, “‘Now it’s my time”: a pivotal pre-game ritual that he now attributes to his win. Ricciardo’s passion for live music has even seen him invest in a 600-person (pre-Covid) music venue in London’s Kings Cross, called Lafayette, with Ben Lovett, his friend and keyboardist from Mumford & Sons.

If anything, 2020 has seen Ricciardo lean further into his hobbies, most recently with his YouTube series ‘No Brakes’. This POV-style travel series, shot between races, sees him hiking, biking and exploring beyond the confines of the racetrack.“I used to rock up and go airport-hotel-racetrack-hotel-airport. I’d travel to all these places and literally wouldn’t see anything,” he says. “I thought that was the right thing to do, keeping disciplined and focused and on a schedule. I realised, in a way, I was abusing the privilege of travel by not making the most of it.”

What’s more, says Ricciardo, a glimpse into this side of his life helps to set a good example for his younger fans – particularly kids who might not be able to go karting, but can still share an interest in Ricciardo’s other passions. “I’m at an age now where I realise younger kids are looking up to me,” he says. “I’m more conscious of setting a good example, whether it’s on a matter of activism, life, health or business… I guess I’m trying to show them there’s a time to be disciplined and focused. But then there’s also a time to switch off and let yourself enjoy life.”

Next year, Ricciardo will move to McLaren. He says the growth of the marque in the last 12 months is what has tempted him there. “They employed a few people who I’ve known from back in the day, who I think are key people for moving them forward. I think that excited me enough and will give me the best chance to compete at the top in the coming years.”

But, he adds, this is not before he does everything in his power to finish what he started at the French team. “I’m hungry for success,” he says. “And when I say success, it’s to win and to prove that I can do this. I really believe I’m the best. I want to prove that I can be World Champion.” When asked what his goals are beyond the racetrack, Ricciardo grins. “Just being completely comfortable with myself... I’m doing things that feel authentic to me, that I’m passionate about, looking for opportunities to build myself as a person and learn more about life.” He smiles again. “At the end of the day, everyone’s just looking for happiness, right?”