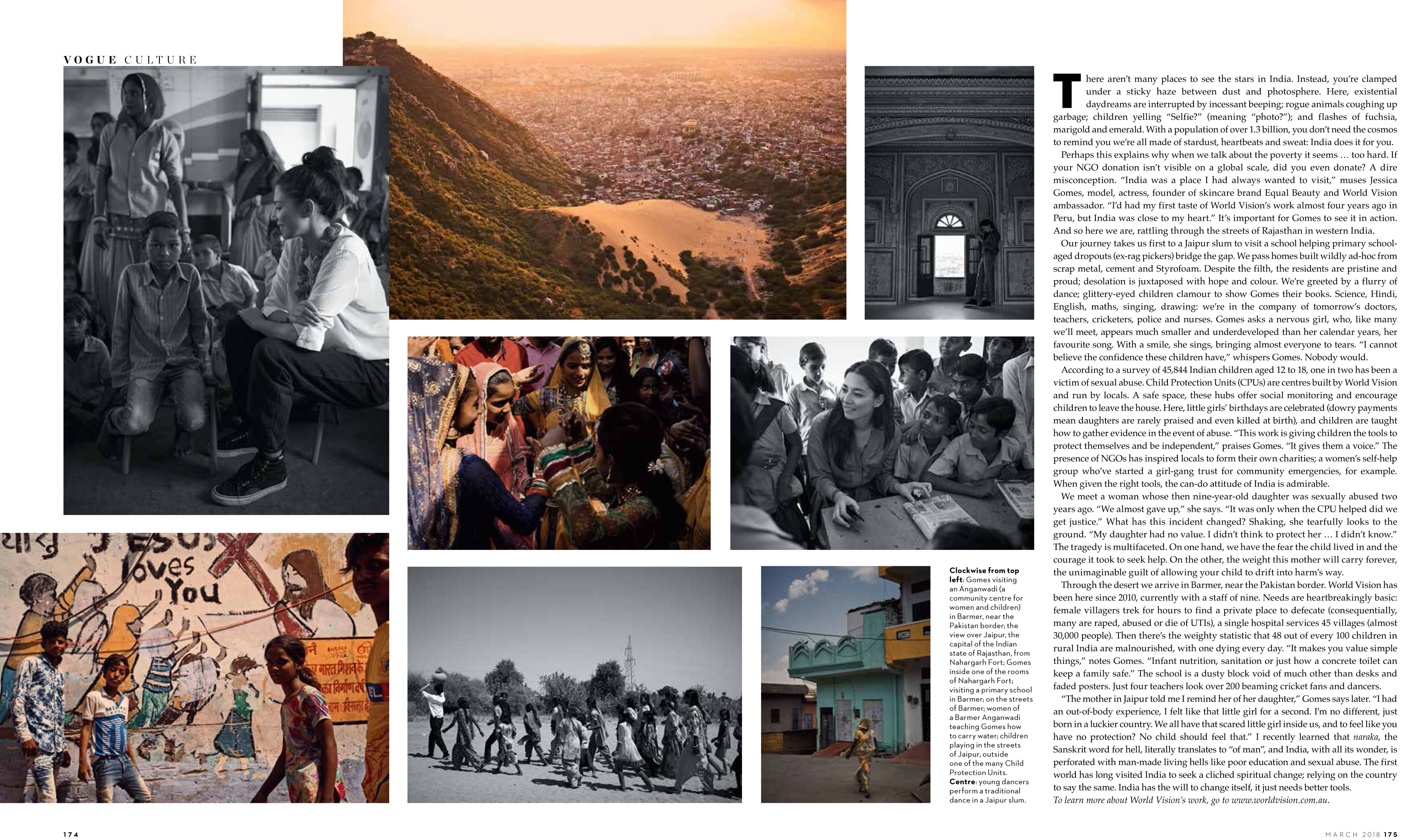

When you sponsor a child, you’re sponsoring a community, but how? World Vision ambassador Jessica Gomes took VOGUE with her to India to witness shifting grassroots. By Noelle Faulkner. Photographs by Jake Terrey.

There aren’t many stars in India. Or rather, there aren’t many places to see the stars. So, unlike travelling to other "spiritual" destinations, looking up to feel small is fruitless. Instead of the divine cosmic veil, you’re clamped thickly under a warm, sticky haze, a strange limbo between the dust of the earth and the sun’s photosphere. Here, existential daydreams are interrupted by the incessant beeping and bustling of seemingly lawless traffic; rogue animals coughing up garbage; children begging to have their photo taken (“Selfie?” they ask, meaning “photo?” – a sign of the times); and flashes of vibrant fuchsia, marigold yellow, Yves Klein blue and emerald green among the crowds. With a population of over 1.3 billion, you don’t need the cosmos to remind you we’re all just made of the same stardust, heartbeats and sweat: India does it for you.

Perhaps this is why the cultural divide between the people and their celebrities is so vast, or why there’s such a desire to be noticed and acknowledged by foreigners, or why when we talk about the poverty problems they seem … too hard. If your NGO donation isn’t visible on a global scale, did you even donate? A dire misconception. Considering the political climate of late, we should all know by now the impact small change can make. “India was a place I had always wanted to visit,” muses Jessica Gomes, model, actress, founder of skincare brand Equal Beauty and World Vision ambassador. “I’d had my first taste of the work that World Vision does almost four years ago when I went to Peru, but India was close to my heart because of all the work they do with women and children.” To be attached to an organisation, it’s important for Gomes to see it in action. And so here we are, rattling through the streets of Rajasthan.

Our journey takes us first to a Jaipur slum, home to artists, dancers, musicians and makers, to visit the children of a remedial school, set up to help primary school-aged dropouts (all ex-child workers and rag-pickers) bridge the gap to a formal education. We pass homes built wildly ad-hoc from scrap metals, cement, what looks like papier-mâché, Styrofoam panels, mud and wire. Almost every adult is tinkering away on something, from woven animals to metal works. Despite the filth, the residents are pristinely clean and proud. A woman apologises for the mess as we catch her taking her washing down, another ushers us to see her humble sewing room. Similarly, this desolation of poverty is juxtaposed with a soaring aura of hope and whirls of colour. We’re greeted by a flurry of dance and music, glittery-eyed children clamour to take Gomes’s hand, showing her their school books. Science, Hindi, English, maths, singing, drawing: we’re in the company of tomorrow’s doctors, teachers, cricketers, police, military and nurses, don’t you know! “What’s your favourite song?” Gomes asks a goofily nervous girl, who, like many we'll meet, appears much smaller and underdeveloped than her calendar years. With a smile, she begins to sing. A beautiful tune that brings almost everyone to tears. “I cannot believe the bright confidence these children have,” whispers Gomes. Considering their past of poverty and garbage sifting, nobody would.

According to a survey of 45,844 Indian children aged 12 to 18, one in every two has been a victim of sexual abuse; with one in every five living in fear. Child Protection Units (CPUs) are centres built by World Vision and run by locals. A safe space, these hubs offer support in the event of a crime, social monitoring and education. They encourage children to leave the house and just be kids. The walls are emblazoned with murals on good touch/bad touch and the government child abuse helpline, and we witness puppet shows and dances preaching peace, empowerment, tolerance, equality and self-worth. Here, little girls’ birthdays are celebrated (dowry payments and lower earnings mean daughters are a burden, rarely praised and even killed at birth), and children are taught how to gather evidence in the event of sexual abuse. “This work is so empowering,” praises Gomes. “It’s giving children the tools to protect themselves and be independent, and it gives them a voice. It’s so important.” The presence of NGOs has inspired local groups to form their own charities, something we see again later in a local women’s self-help group who, thanks to some financial education by World Vision, started their own democratic girl gang trust for community emergencies. It's worth noting the can-do attitude of this culture with the bare minimum materials.

We're introduced to a woman whose then-9-year-old daughter was sexually abused two years ago. “We almost gave up,” she says, clutching the hands of a girlfriend. “It was only when the CPU helped did we get justice.” What has this incident changed and what has she learned? Shaking, with tears in her eyes, she looks to the ground. “My daughter had no value. I didn’t think to protect her … I didn’t know.” Like much of what we’re seeing, the tragedy of this situation is multifaceted. On one hand we have the fear the child lived in and the courage it took to seek help. On the other, the weight this mother will carry forever, the unimaginable guilt of allowing your child to drift into harm’s way.

A two-hour road trip from Jodhpur of sand, greenery and wandering highway camels, cows and buffalo takes us to Barmer, a desert city near the Pakistan border with a population of over 44,000. World Vision has been here since 2010, currently with a staff of nine. Needs are at their heartbreakingly basic: lack of toilets mean female villagers trek two to five kilometres to find a safe and private place to defecate (consequentially, many are raped, abused or die of UTIs), while a single small hospital services 45 villages (almost 30,000 people). Then there’s the weighty statistic that 48 out of every 100 children in rural India are malnourished, with one dying every day. “It makes you value simple things,” notes Gomes on the work that the NGO is doing here. “Teaching about infant nutrition and breastfeeding and how to boil water or just how building a family a concrete toilet that will keep them safe from harm.” The women congregate at their local Angan-Bari, a small building where children, mothers and teens can hang out, seek support for infant and female health, or talk fashion, music and marital life. “I wish I had something like this in LA!” laughs Gomes. The local primary school is a dusty, concrete block void of much other than desks and some faded animal posters. Just four teachers look over 200 beaming faces, who are gushing about cricket, explaining what appears to be a version of playground game bullrush and talking about what they do on their multiple-kilometre walks to school. A blackboard curiously reads: “Outside the class. Only meaning.” Despite the major progress here, it's bittersweetness seeped in hope.

“You know, the mother in Jaipur told me I remind her of her daughter,” Gomes says later. “I had an out-of-body experience, I felt like that little girl for a second. I’m no different from her or any of these women, just born in a luckier country. We're all the same, fighting the same things! We all have that scared little girl inside us, and to feel like you have no protection? No child should feel that.”

I recently learned that naraka, the Sanskrit word for hell literally translates to “of man"; which felt on-point for what we've seen. India, with all it’s historic romantic wonder, colour, flavour and spirituality, is perforated with man-made living hells for women and children: poverty, abuse and a lack of hygiene, nutrition and education.

They say that after you visit India everything changes and the first world has long visited sought out this cliché; relying on the country to say the same. India has the will to change itself, it just needs better tools.

To learn more about World Vision’s work, go to www.worldvision.com.au.

*An edited version of the above appeared in VOGUE Australia's March 2018 issue, guest edited by Emma Watson.