Type7 Volume 2, 2020 (coffee table book, a collaboration with Porsche, as contributor and copy editor)

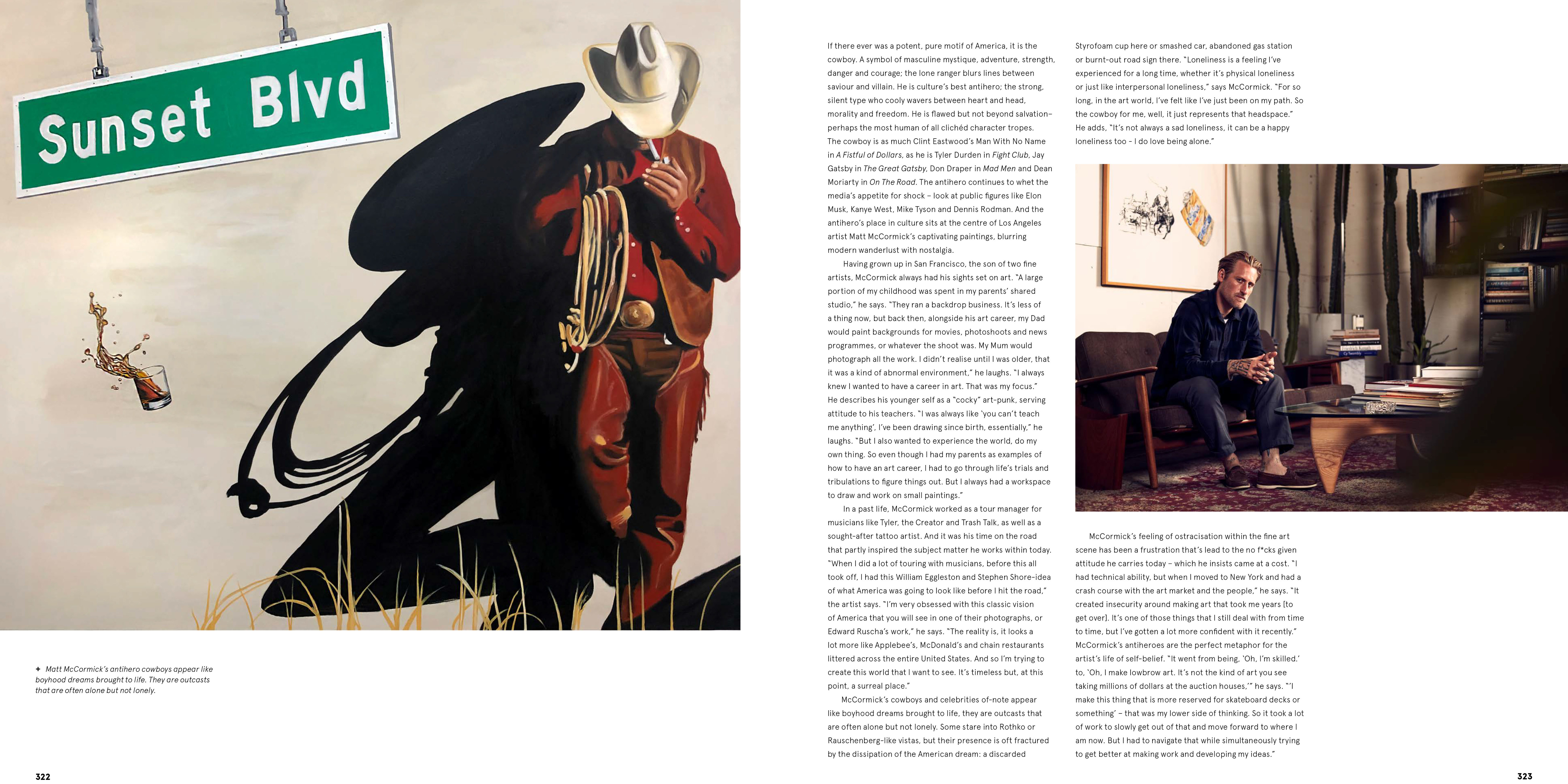

If there ever was a potent, pure motif of America, it is the cowboy. A symbol of masculine mystique, adventure, strength, danger and courage; the lone ranger blurs lines between saviour and villain. He is culture’s best antihero; the strong, silent type who cooly wavers between heart and head, morality and freedom. He is flawed but not beyond salvation– perhaps the most human of all clichéd character tropes.

The cowboy is as much Clint Eastwood’s Man With No Name in A Fistful of Dollars, as he is Tyler Durden in Fight Club, Jay Gatsby in The Great Gatsby, Don Draper in Mad Men and Dean Moriarty in On The Road. The antihero continues to whet the media’s appetite for shock – look at public figures like Elon Musk, Kanye West, Mike Tyson and Dennis Rodman. And the antihero’s place in culture sits at the centre of Los Angeles artist Matt McCormick’s captivating paintings, blurring modern wanderlust with nostalgia.

Having grown up in San Francisco, the son of two fine artists, McCormick always had his sights set on art. “A large portion of my childhood was spent in my parents’ shared studio,” he says. “They ran a backdrop business. It’s less of a thing now, but back then, alongside his art career, my Dad would paint backgrounds for movies, photoshoots and news programmes, or whatever the shoot was. My Mum would photograph all the work. I didn’t realise until I was older, that it was a kind of abnormal environment,” he laughs. “I always knew I wanted to have a career in art. That was my focus.”

He describes his younger self as a “cocky” art-punk, serving attitude to his teachers. “I was always like ‘you can’t teach me anything’, I’ve been drawing since birth, essentially,” he laughs. “But I also wanted to experience the world, do my own thing. So even though I had my parents as examples of how to have an art career, I had to go through life’s trials and tribulations to figure things out. But I always had a workspace to draw and work on small paintings.”

In a past life, McCormick worked as a tour manager for musicians like Tyler, the Creator and Trash Talk, as well as a sought-after tattoo artist. And it was his time on the road that partly inspired the subject matter he works within today. “When I did a lot of touring with musicians, before this all took off, I had this William Eggleston and Stephen Shore-idea of what America was going to look like before I hit the road,” the artist says. “I’m very obsessed with this classic vision of America that you will see in one of their photographs, or Edward Ruscha’s work,” he says. “The reality is, it looks a lot more like Applebee’s, McDonald’s and chain restaurants littered across the entire United States. And so I’m trying to create this world that I want to see. It’s timeless but, at this point, a surreal place.”

McCormick’s cowboys and celebrities of-note appear like boyhood dreams brought to life, they are outcasts that are often alone but not lonely. Some stare into Rothko or Rauschenberg-like vistas, but their presence is oft fractured by the dissipation of the American dream: a discarded Styrofoam cup here or smashed car, abandoned gas station or burnt-out road sign there. “Loneliness is a feeling I’ve experienced for a long time, whether it’s physical loneliness or just like interpersonal loneliness,” says McCormick. “For so long, in the art world, I’ve felt like I’ve just been on my path. So the cowboy for me, well, it just represents that headspace.” He adds, “It’s not always a sad loneliness, it can be a happy loneliness too - I do love being alone.”

McCormick’s feeling of ostracisation within the fine art scene has been a frustration that’s lead to the no f*cks given attitude he carries today – which he insists came at a cost. “I had technical ability, but when I moved to New York and had a crash course with the art market and the people,” he says. “It created insecurity around making art that took me years [to get over]. It’s one of those things that I still deal with from time to time, but I’ve gotten a lot more confident with it recently.” McCormick’s antiheroes are the perfect metaphor for the artist’s life of self-belief. “It went from being, ‘Oh, I’m skilled.’ to, ‘Oh, I make lowbrow art. It’s not the kind of art you see taking millions of dollars at the auction houses,’” he says. “’I make this thing that is more reserved for skateboard decks or something’ – that was my lower side of thinking. So it took a lot of work to slowly get out of that and move forward to where I am now. But I had to navigate that while simultaneously trying to get better at making work and developing my ideas.”

The beautiful irony now is, as an unrepresented artist, McCormick sells, collaborates and exhibits with full autonomy while also cultivating a database of collectors via Instagram. “It’s how everyone is viewing art right now anyway,” he says matter-of-factly. “There’s no gallery system that’s truly got a physical advantage because we can’t go to galleries like we used to. It’s an interesting time to see how people are exchanging, seeing and presenting art. “With McCormick’s body of work in mind, it seems crazy for anyone to have ever underestimated the painter’s success. “We’re in a time where there’s an old guard and a new guard,” he shrugs. “I want to make art that you don’t need an art theory degree to enjoy. But if you do, you can enjoy it as well... I think lots of people are trying to figure out that median now.”

Aside from sheer talent, McCormick wears his deep knowledge of art history on his sleeve. “It’s important to know what came before you,” he says. “Look at cars,” he says. “You don’t just look at the cars that are out right now. If you don’t look at what came before, how do you learn? I obsess over how I can respond to the work that came before me.” Arriving at the crossroads of many of the American greats, McCormick’s vision of his home country comes with shades of Edward Hopper, Fairfield Porter, Mark Rothko, Richard Prince and Eggleston. “A big thing for me now is using art history to help influence the way I’m making these paintings,” he says, citing Philip Guston, Lucien Freud and Cy Twombly as recent fixations. “I’m a figurative painter in most people’s eyes, but I’ve always had an attraction to abstraction. I’m always trying to figure out ways to incorporate that into my work,” he says. “Some of my recent paintings have pop culture references, and it’s funny because surrealism and pop aren’t my favourites. Not that I don’t like them, but they’re not what I’d choose to hang in my house. So it’s been interesting to analyse my work and go, ‘Wow, my work is starting to fit into this weird surrealist pop space.’” He laughs. “But that’s just what I feel inclined to make, and what I’m enjoying making. It’s very subconscious.”

With McCormick’s generation, the romance of Americana-past is now nothing but an old-timey pantomime. Still, the magnetism of big skies and open plains has curiously returned – this is the full circle shift McCormick speaks to now. “I think the cowboys embody that space,” he says. “It goes back to painting the world that I want to live in. Not that I want to spend the rest of my life alone riding a horse across the range, but we’re just so inundated with information all the time, it’s now this goal of mine to find the quiet. To be out within nature and be able to have this quiet place... I think we can all agree the loudness of the world is very overwhelming at times. And so I’m painting this idea, this dream space that can feel so hard to obtain.”