Type7 Volume 2, 2020 (coffee table book, a collaboration with Porsche, as contributor and copy editor)

“This is Major Tom to Ground Control, I’m stepping through the door, And I’m floating in a most peculiar way, And the stars look very different today,” David Bowie sings on Space Oddity. Inspired by Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Oddity, 51 years on, the iconic track still stirs the heart. Because if the first half of 2020 symbolised anything, it was the relinquishment of control and a desire for escape.

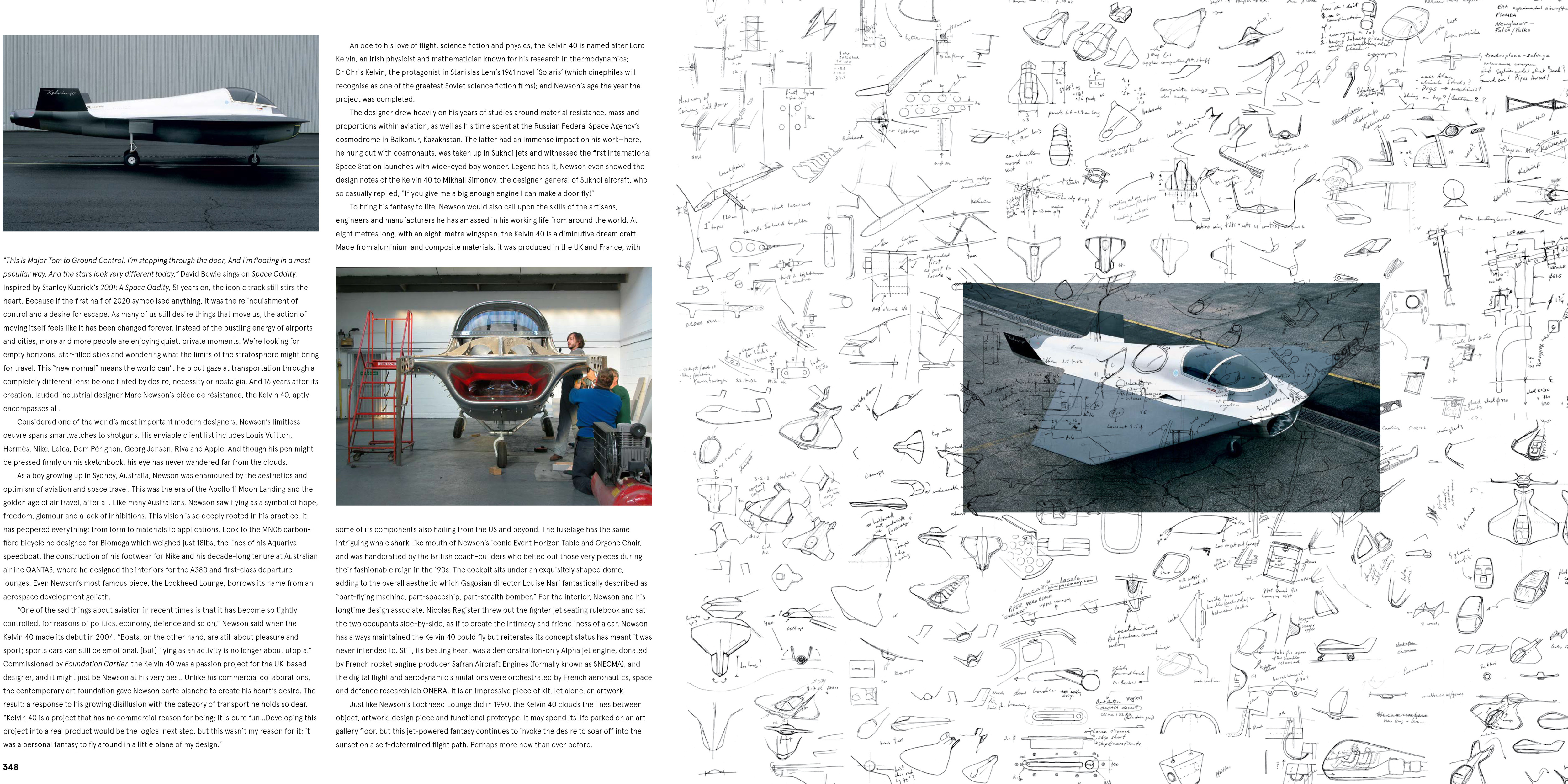

As many of us still desire things that move us, the action of moving itself feels like it has been changed forever. Instead of the bustling energy of airports and cities, more and more people are enjoying quiet, private moments. We’re looking for empty horizons, star-filled skies and wondering what the limits of the stratosphere might bring for travel. This “new normal” means the world can’t help but gaze at transportation through a completely different lens; be one tinted by desire, necessity or nostalgia. And 16 years after its creation, lauded industrial designer Marc Newson’s pièce de résistance, the Kelvin 40, aptly encompasses all.

Considered one of the world’s most important modern designers, Newson’s limitless oeuvre spans smartwatches to shotguns. His enviable client list includes Louis Vuitton, Hermès, Nike, Leica, Dom Pérignon, Georg Jensen, Riva and Apple. And though his pen might be pressed firmly on his sketchbook, his eye has never wandered far from the clouds.

As a boy growing up in Sydney, Australia, Newson was enamoured by the aesthetics and optimism of aviation and space travel. This was the era of the Apollo 11 Moon Landing and the golden age of air travel, after all. Like many Australians, Newson saw flying as a symbol of hope, freedom, glamour and a lack of inhibitions. This vision is so deeply rooted in his practice, it has peppered everything; from form to materials to applications. Look to the MN05 carbon- fibre bicycle he designed for Biomega which weighed just 18lbs, the lines of his Aquariva speedboat, the construction of his footwear for Nike and his decade-long tenure at Australian airline QANTAS, where he designed the interiors for the A380 and first-class departure lounges. Even Newson’s most famous piece, the Lockheed Lounge, borrows its name from an aerospace development goliath.

“One of the sad things about aviation in recent times is that it has become so tightly controlled, for reasons of politics, economy, defence and so on,” Newson said when the Kelvin 40 made its debut in 2004. “Boats, on the other hand, are still about pleasure and sport; sports cars can still be emotional. [But] flying as an activity is no longer about utopia.” Commissioned by Foundation Cartier, the Kelvin 40 was a passion project for the UK-based designer, and it might just be Newson at his very best. Unlike his commercial collaborations, the contemporary art foundation gave Newson carte blanche to create his heart’s desire. The result: a response to his growing disillusion with the category of transport he holds so dear. “Kelvin 40 is a project that has no commercial reason for being; it is pure fun...Developing this project into a real product would be the logical next step, but this wasn’t my reason for it; it was a personal fantasy to fly around in a little plane of my design.”

An ode to his love of flight, science fiction and physics, the Kelvin 40 is named after Lord Kelvin, an Irish physicist and mathematician known for his research in thermodynamics; Dr Chris Kelvin, the protagonist in Stanislas Lem’s 1961 novel ‘Solaris’ (which cinephiles will recognise as one of the greatest Soviet science fiction films); and Newson’s age the year the project was completed.

The designer drew heavily on his years of studies around material resistance, mass and proportions within aviation, as well as his time spent at the Russian Federal Space Agency’s cosmodrome in Baikonur, Kazakhstan. The latter had an immense impact on his work—here, he hung out with cosmonauts, was taken up in Sukhoi jets and witnessed the first International Space Station launches with wide-eyed boy wonder. Legend has it, Newson even showed the design notes of the Kelvin 40 to Mikhail Simonov, the designer-general of Sukhoi aircraft, who so casually replied, “If you give me a big enough engine I can make a door fly!”

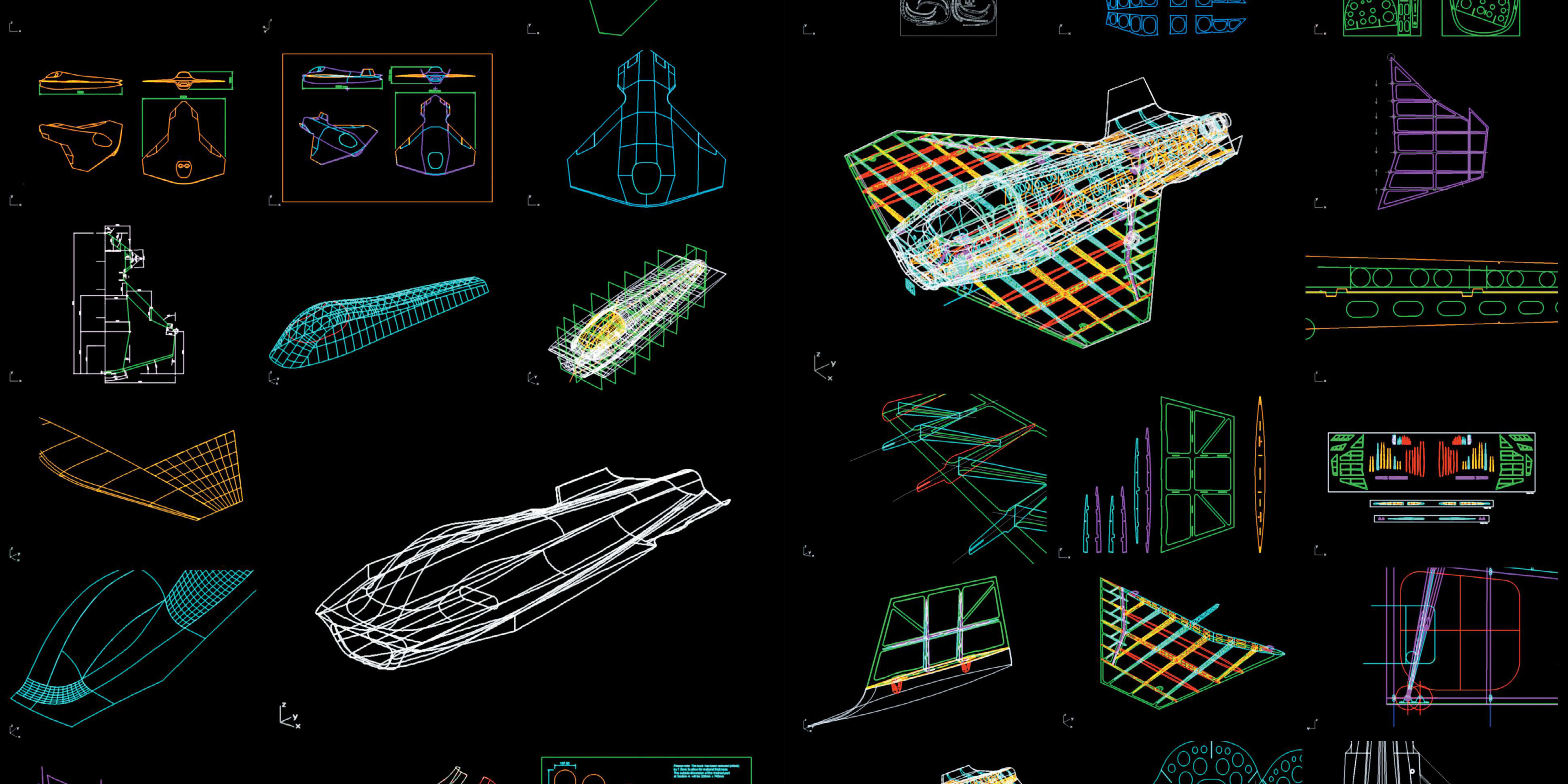

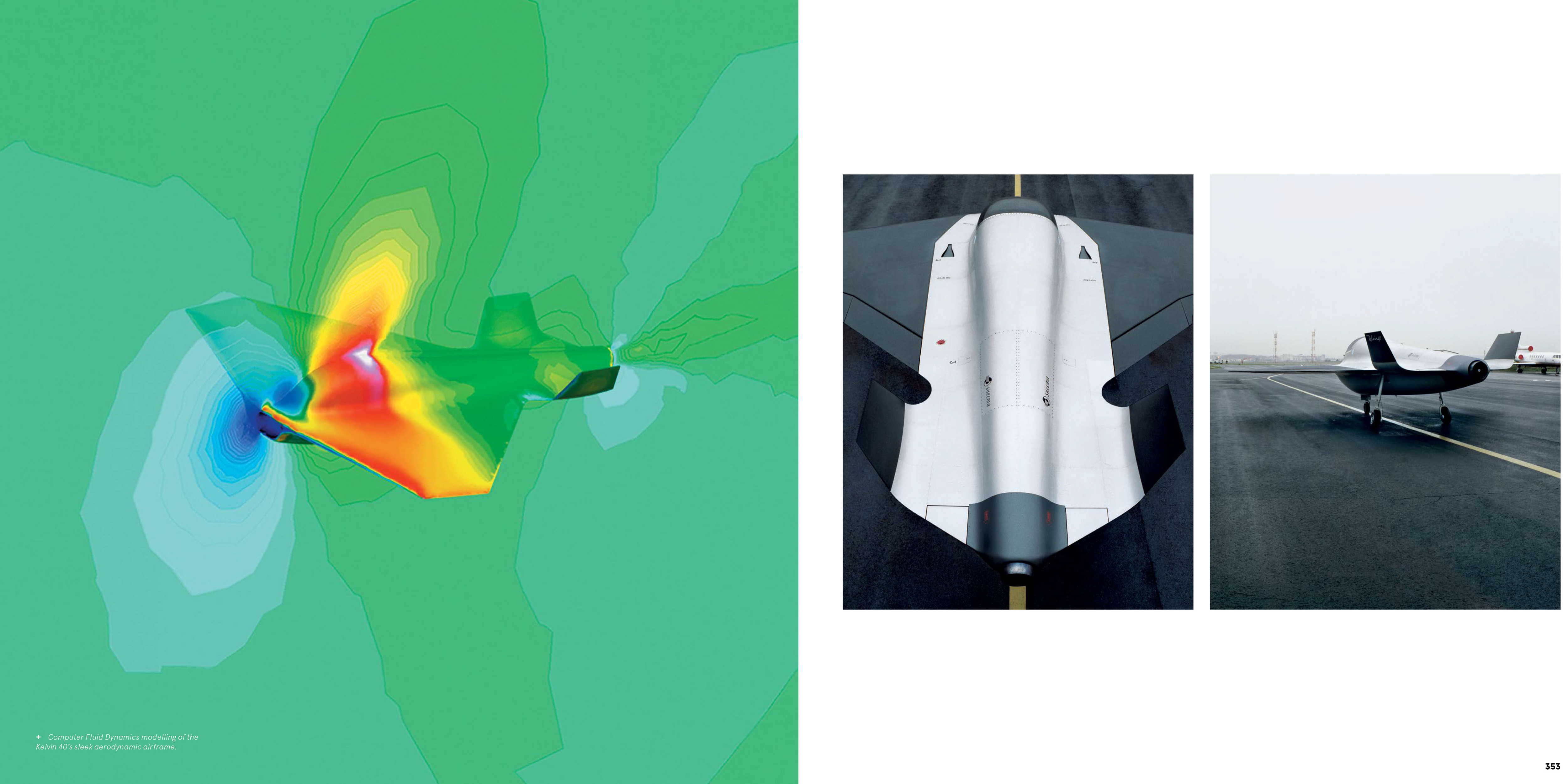

To bring his fantasy to life, Newson would also call upon the skills of the artisans, engineers and manufacturers he has amassed in his working life from around the world. At eight metres long, with an eight-metre wingspan, the Kelvin 40 is a diminutive dream craft. Made from aluminium and composite materials, it was produced in the UK and France, with some of its components also hailing from the US and beyond. The fuselage has the same intriguing whale shark-like mouth of Newson’s iconic Event Horizon Table and Orgone Chair, and was handcrafted by the British coach-builders who belted out those very pieces during their fashionable reign in the ‘90s. The cockpit sits under an exquisitely shaped dome, adding to the overall aesthetic which Gagosian director Louise Nari fantastically described as “part-flying machine, part-spaceship, part-stealth bomber.” For the interior, Newson and his longtime design associate, Nicolas Register threw out the fighter jet seating rulebook and sat the two occupants side-by-side, as if to create the intimacy and friendliness of a car. Newson has always maintained the Kelvin 40 could fly but reiterates its concept status has meant it was never intended to. Still, its beating heart was a demonstration-only Alpha jet engine, donated by French rocket engine producer Safran Aircraft Engines (formally known as SNECMA), and the digital flight and aerodynamic simulations were orchestrated by French aeronautics, space and defence research lab ONERA. It is an impressive piece of kit, let alone, an artwork.

Just like Newson’s Lockheed Lounge did in 1990, the Kelvin 40 clouds the lines between object, artwork, design piece and functional prototype. It may spend its life parked on an art gallery floor, but this jet-powered fantasy continues to invoke the desire to soar off into the sunset on a self-determined flight path. Perhaps more now than ever before.