10+ Magazine, December 2019 (PDF)

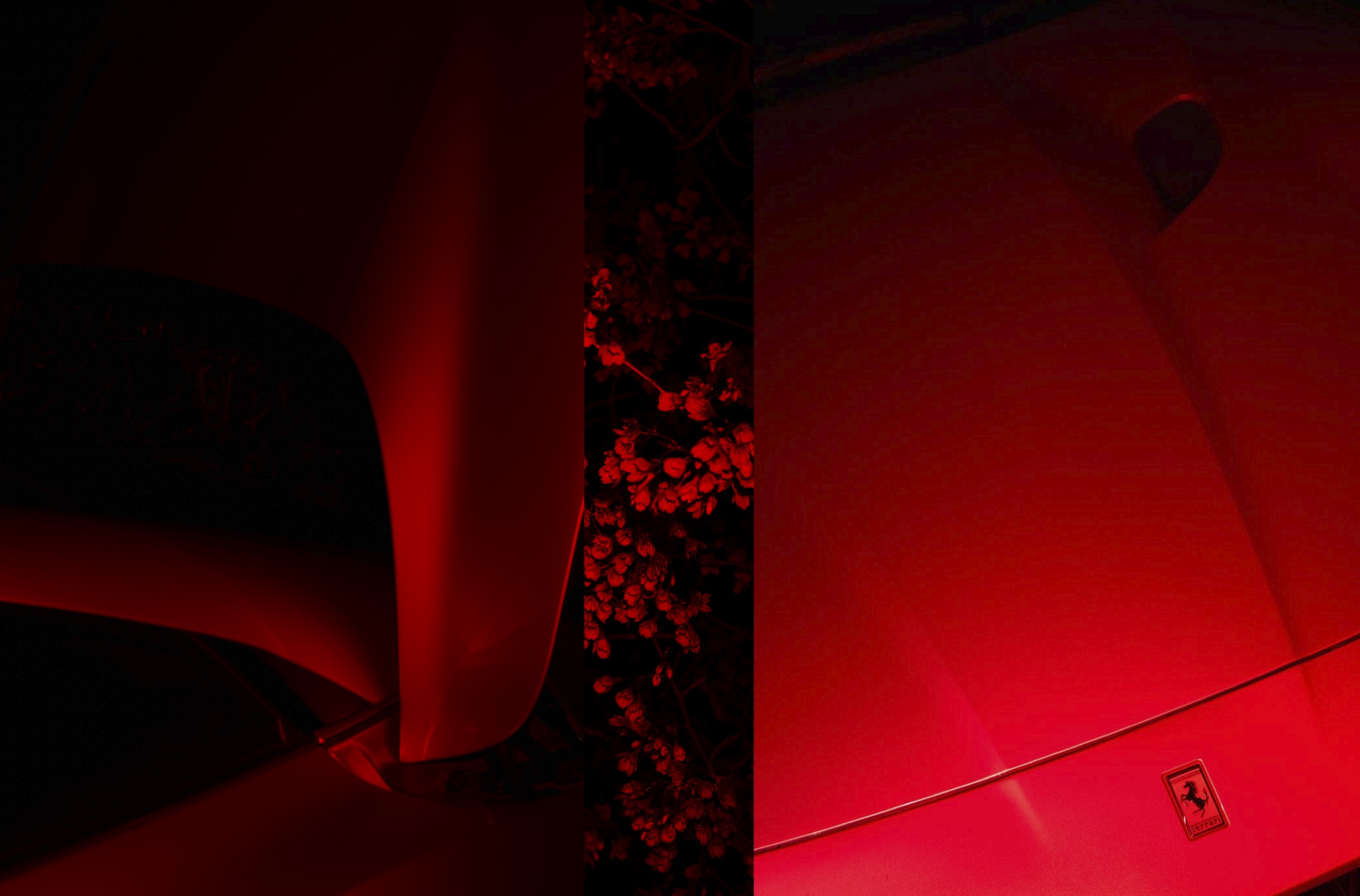

If the Ferrari Portofino is anything, it’s the synthesis and distillation of its homeland: taste, passion, freedom, romance, history, art and the unashamed pursuit of pleasure. Lower the roof, throw away your schedule and light up the road – you’re on Italian time now.

There are things nobody warns you about Maranello. People just tell you to go. Maranello is one of those places like Paisley Park, Kennedy Space Centre, the church and convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie or Museo Galileo. It’s hallowed ground for those with science, art or emotion in their blood and home to one of the most significant inventions in the world: FerrariTM.

Ferrari is the most recognisable brand on the globe and Maranello is Ferrari’s crucible. It is where its founder, Enzo Ferrari, spent almost all of his days; it is where rosso corsa became more than just a shade of red; and it is where metal is shaped into some of the world’s most desired machines. Maranello is particularly special for the residents of nearby historic Modena, Emilia-Romagna, in northern Italy. Here, hearts beat as hard for the prancing horse as they do for balsamic vinegar.

The Ferrari factory itself is a sight to behold, filled with workers identically dressed in red jumpsuits; it is a shrine to modern, man-made wonders. The Formula One room, containing every one of its F1 cars made in history, will make you cry. The clinically pristine factory, with all its craftsmanship and precision, will enthral you. The ghosts in the walls will whisper in your ears the true meaning of influence and passion. While the birthplace of that prancing horse is exceptionally special, the inescapable truth about Maranello is that one can’t feel four-wheeled, fuel-injected freedom standing next to a robotic arm.

My first experience behind the wheel of a Ferrari actually happened to be on the twisting roads of Emilia-Romagna. I was handed the fabled red key to a V12 GTC4 Lusso at the Ferrari factory and nonchalantly told, “Just bring it back later, darlink, someone will be here. Ciao! Ciao!” It was, coincidently, my birthday, which is in December. There was black ice and snow – not an ideal combination when you’re sitting on 680 horses’ worth of power, or is it? You see, the roads of Ferrari’s home do not suffer fools. They snake into small villages, narrow and sharp. There are blind corners, potholes, terribly parked Fiat Pandas and aggressive milkmen peddling their vans at you to dodge. These streets will test you and your skills – they certainly pushed me to test mine, as well as the capabilities of my cavallino-stamped supercar. That feeling where you’re in the zone and acutely mindful of every rev and bump and corner and angle is like no other. Your abs tense, pupils widen and heart beats, and your smile becomes unbreakable – particularly if you’re totally alone, as I was. This is the thrill of driving magnificent machines. You see, the open road is where the true intention of a Ferrari, beyond a racetrack of course, is revealed. Ferrari’s mechanical objects of poise and strength demand attention, but are not designed with the spectator in mind; their allure makes you want to go places, but the destination is irrelevant. And while they might be future-glancing, God forbid Ferrari should succumb to the automatous revolution.

Human movement, carnal pleasure, control and boldness tell this story. And you know what? Despite what the Modena tourism board tells you, you don’t need to visit Maranello to evoke the Ferrari spirit of mystique, beauty, craftsmanship and deliciously addictive danger. You only need to press a little red button.

Ferrari is often associated with the angular, wedge-like shapes seen on the F40 and the Testarossa – the iconic poster cars of the 1980s. But it’s a curious and little-known fact that the first road car produced by Ferrari was actually a convertible made in 1947. The Ferrari 125 S was a two-seater Spyder race car, with long, forward-leaning haunches, bug-eye lights and Enzo’s first V12 engine. This car evolved into the equally adorable and spritely 166. For the competitive and trophy-focused Enzo, the 166 was the first car to earn him the one thing he truly desired: a real racing pedigree. But it led the way for wind-in-your-hair freedom and performance, done best with a passenger by your side (as we discovered on the dark back roads of NSW’s Southern Highlands in our Portofino).

The convertible is the universal symbol of wild abandon. It’s in the audacity of not even needing to open a door to get in. It’s in the dust and sun that hits Thelma and Louise in their 1966 Ford Thunderbird during their fateful desert jaunt. It’s in the ballet that Grace Kelly’s scarf performs in the wind while she’s rocketing through the French Riviera in a 1953 Sunbeam Alpine in To Catch a Thief. And let’s not forget the mistress of temptation in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off: a 1961 Ferrari 250 California Spyder. One of Ferrari’s most beautiful cars, this embodies the spirit of the convertible – the unadulterated pursuit of pleasure.

A highly-desired car for collectors around the world, Ferris' femme fatale is a vessel for the imagination. The 250 California Spyder is a machine one falls in love with and within. Its long lines and curved rear, designed by Pinin Farina, possess an essence of romance only the Côte d’Azur usually provokes. Even two of French cinema’s most seductive actors of the time it was produced, Brigitte Bardot and Alain Delon, owned one. It is the roadster you can see yourself in, caught in a summer love affair you never want to expire. But no matter how at home it looked in the Mediterranean, it was aimed at tempting Americans away from their wide-bodied, boat-like cruisers (hence the name), and it certainly made those across the Atlantic pay attention. In more ways than one, it is the cousin to what has become one of Ferrari’s most important cars today: the Portofino.

In the same way that fashion’s codes are reinterpreted for a new season, certain cues have come to define the Portofino. This hard-topped convertible is a stunning homage to Ferrari design. The round taillights are a tribute to the F40, the front end echoes the newer 488’s nose, and the low sides and voluptuous rear rises up like that of the 250 California. As the baby Ferrari (and the most affordable) and the replacement for the 2008-revealed California T (but much, much better), the Portofino has attracted scores of new buyers to Ferrari – it is the gateway drug to an all- consuming prancing-horse habit. And what a drug. With a 3.9-litre, 441kW and 760Nm-producing twin-turbocharged V8 with that signature Ferrari baritone, the ability to launch 0-100km/h in 3.5 seconds, and sharp and direct steering borrowed from its supercar siblings, it is in every sense worthy of its badge. Being a grand tourer, it yearns to be let out of the gate and into the wild. I have driven this car on track and on the road, and every time it is the same: with the start of that engine, two hands sliding across that wheel, and the flex of the right foot, every worry, anxiety or deadline is shot out of the exhaust, shaken off past the lowered roof and left in the dust. And the Portofino is glamour and top-down spontaneity, just like its little red ancestor.

On paper, convertibles equal glamour. Think dusty pink sunsets and traffic-free roads, a passenger staring longingly out the side while their hand catches and releases the wind, or three passengers with windswept hair and sunlit grins. Of course, the reality is much more different, involving bugs and dirt and matted hair – but that is also part of the top-down courtship, by the way. However, glamour seems to also be a high priority for Maranello right now. The past year alone, style has featured high on the agenda, as well as the release of five exquisite new models. On the one hand, there is the sparkle of Scuderia Ferrari’s golden child, the 22-year-old Monégasque F1 racing driver, Charles Leclerc. Signed to Ferrari for 2019, he embodies that nonchalant, racing-driver sex appeal, a star-based formula not seen in the sport since the days of James Hunt (although Leclerc’s distillation is a lot more appropriate for 2019 – “Make it Timothée Chalamet, but racing.”) There is the Australian-led gender-diversity initiative, Ferrari Driven Women, which launched in 2018 and has hosted a track day for female customers only (fun fact: Australia has the highest percentage of female Ferrari owners in the world at 9%). Then there was Universo Ferrari, a huge exhibition that invited VIPs and enthusiasts into the secret halls of Maranello and kicked off with a party to rival those of Milan Fashion Week. It’s enough to wonder what race-obsessed Enzo, who allegedly (and somewhat unromantically) summed up his craft by saying, “I build engines and attach wheels to them,” would have said about all this.

Of course, we can talk about brand power until we run out of gas, but is it all about that? Not really. Cars, super or not, offer more than the logo stamped on the front. In their purest essence, they are a gateway to liberation, mindfulness and empowerment, not to mention a private celebration of control. Modern discourse talks about digital detoxing and addiction to screens – well, the antidote is right in our driveways. While the romance of something like the 250 California Spyder might be missing, we can at least be satisfied that the modern motor, such as the Portofino, is safer, faster and still beautiful.

A car is the only form of modern art designed to come alive with the warm touch of human flesh and beating pulse through thumbs placed at three and nine – and sure, it does get more exciting when you lose the roof. As Ferris Bueller so aptly put it, “Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.”