10Men Magazine, March 2021 (PDF)

In a relatively Covid-19-free Australia, big-ticket items have taken the place of big vacations, driving up luxury-car sales, home renovations and the return of the great Australian dream of homeownership. Enter a spiked interest in Australian designers, retailers and makers.

Things are starting to change a little here,” says Richard Munao, founder and man- aging director at designer-furniture retailer Cult. “In the past, there has been this cultural thing in Australia where people won’t pay more for products made to last.” This, Munao says, ends up not only hurting designers but the cogs of the essential local manufacturing industry. “Look at Denmark, where around 80% of our imported collection is from – it’s part of the culture there. People will pay more for pieces that have a story behind them, that are made well and have a history of how they’ve been used.”

The pandemic reinvigorated interior design globally – beyond Zoom-call backgrounds and WFH setups. Instead of the flaunting of the season’s key fashion pieces at the shows, we saw into fashion’s home. Insta clout moved to become an interior-design-by-numbers event, furniture the new fashion. The 2020 bingo sheet? Ettore Sottsass’s wavy, neon-lit Ultrafragola mirror; Le Corbusier’s boxy LC2 armchair; the squishy, long Togo sofa; and the charming Murano mushroom lamp. As such, thrifting is peaking, thanks to Facebook Marketplace, Depop and Instagram. Of course, the downside of desirable design is the inevitable wave of replicas. Munao’s solution: Cultivated, Cult’s resale initiative that is both a buyback and resell programme, offering authentic secondhand pieces refurbished by local craftsman trained in Denmark by the actual manufacturers. “You still get that stamp of authenticity. It’s supporting local businesses and craftsman, it’s reducing the impact of having to send furniture to Denmark or wherever it’s from,” he explains. “And it’s an education thing – we want Australians to see the quality of authentic design – whether it’s Australian, like what we do with [our own brand] Nau, or not. People do notice the difference. But by doing this, we’re extending the life of these pieces, while also making them more affordable.”

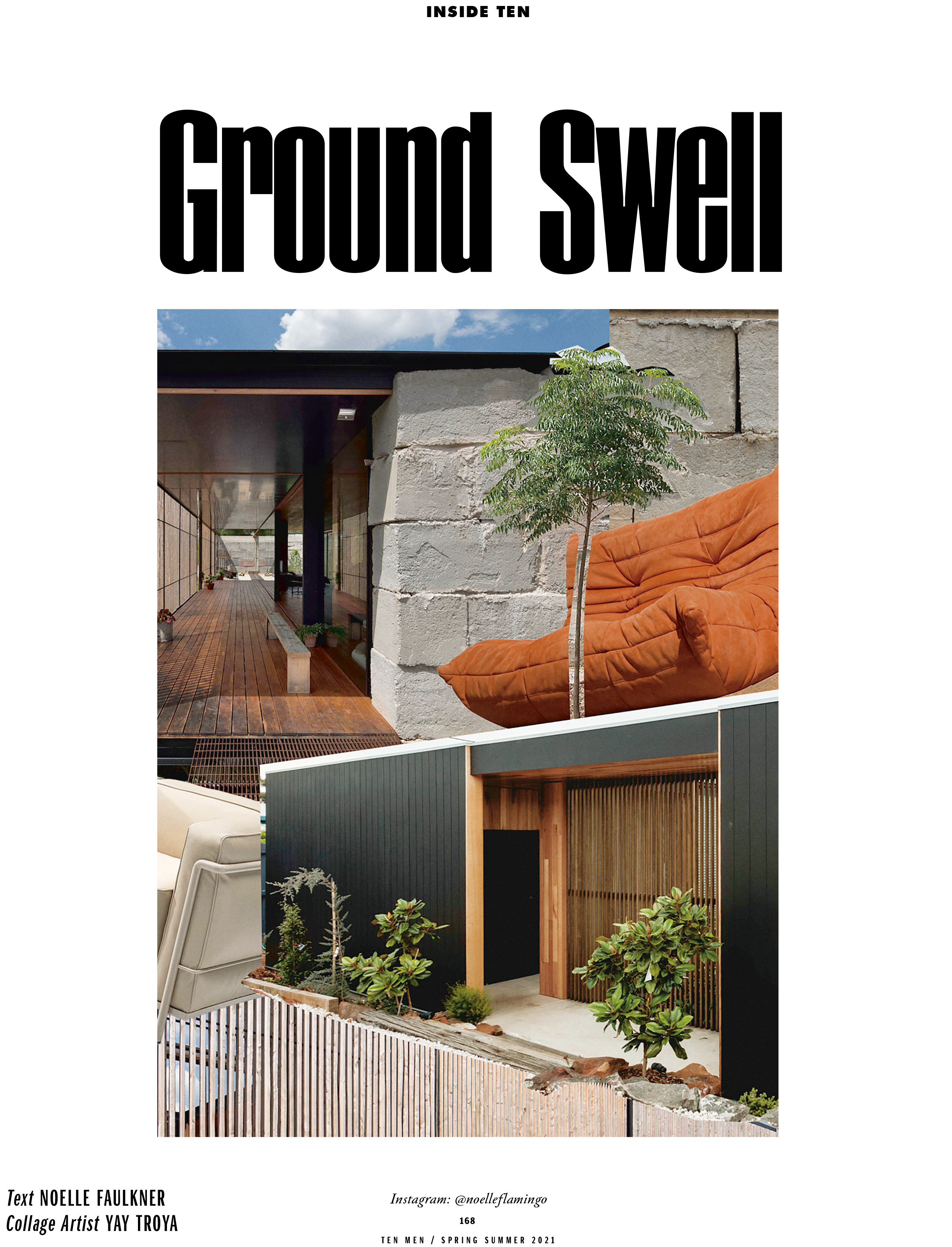

While the rest of the developed world reached for soft and fluffy comfort, Australians yearned to be closer to the great outdoors, finding comfort in rays of sun and woods, inside and out. Once considered niche, the desire for sustainable practices, natural materi- als and design-in-retrospect has entered the mainstream – the decline of the McMansion in favour of simpler times, like Robin Boyd’s modernist Australia, is nigh. “There’s this idea of the ‘designer-maker’, which harks back to the early modernist architects that used to design homes, as well as the cutlery sets, the furniture and the lights,” says Chris Haddad, a director at Melbourne design firm Archier, noting that this has been something the agency has been doing since its Grand Designs-famous Sawmill House of 2015. “For us, this process of learning-by-making has been fundamental, and it resonated with a lot of new clients that we were makers ourselves, we were using local trades and collaborating end-to- end with local craftsman. There has, for a few years now, been this interest coming back to local makers, where people are moving away from mass-produced lighting and mass- produced products and looking for something handmade with a level of love to it.”

If anything, Australia’s new-found self-interest has led to one collective thought that has permeated design: how can we build for a future we’re proud of, one we don’t have to look across the sea for? Be that in the design of our homes, the styling of our rooms, the products we buy or how we interact with the world around us. “What we’re seeing now is everything that design and architecture should be about – it’s certainly what our main purpose is,” says Haddad. “And that’s creating spaces that deliver a better quality of life. It really is as simple as that.”