10 Magazine, March 2021 (PDF)

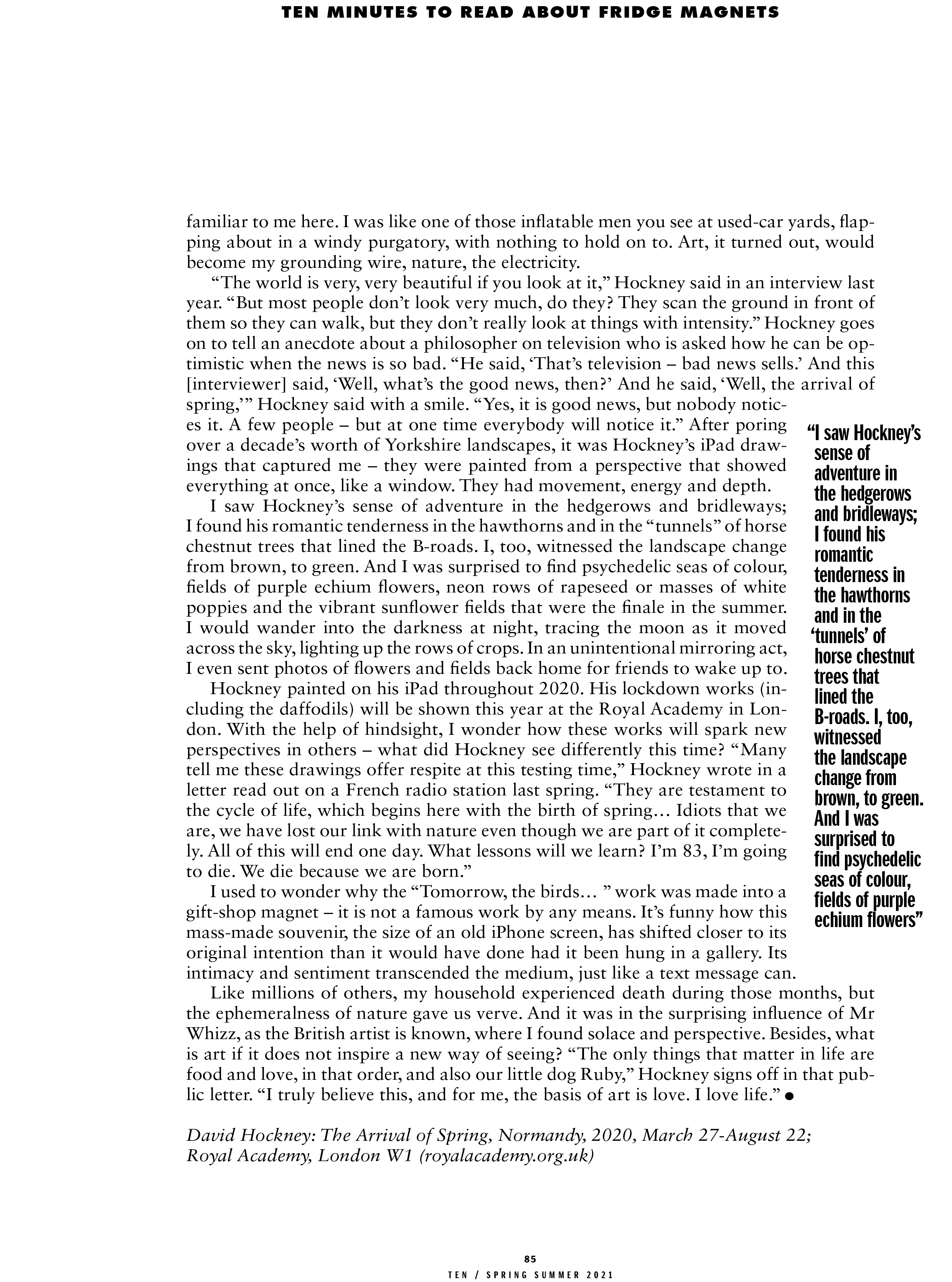

“Tomorrow the birds will sing. Love David.” Thumbed onto an iPhone by David Hockney in 2009, printed onto a magnet, sold near the exit of an art gallery, purchased and then placed by me at eye level on my refrigerator at home, next to a postcard of The Dream by Henri Rousseau. I read these words every day.

The magnetised avowal is a reproduction of hundreds of little iPhone drawings that Hockney draws in his Brushes app, which he then texts to his friends every morning. His favourite thing to send is flowers, so that his loved ones get a bunch of fresh blooms every day. Imagine waking up to a Hockney original via text each morning. “Good morning! Love life, David.”

The words written on my Hockney magnet were also spoken (well, mouthed) by Char- lie Chaplin in the 1931 film City Lights. In the scene, a tramp (Chaplin) stumbles upon an intoxicated man trying to commit suicide by a canal and steps in to prevent the act. Chaplin’s words “Tomorrow the birds will sing” flash on a slide. “Be brave! Face life!” It’s not known if Hockney was directly referencing Chaplin via his hand-drawn MMS and, until I discovered this, it had never occurred to me that Chaplin and Hockney might have been born into similar orbits. However, their art is parallel in that it has brought joy while standing for all that is good. With a dose of impeccable timing, too, it would seem.

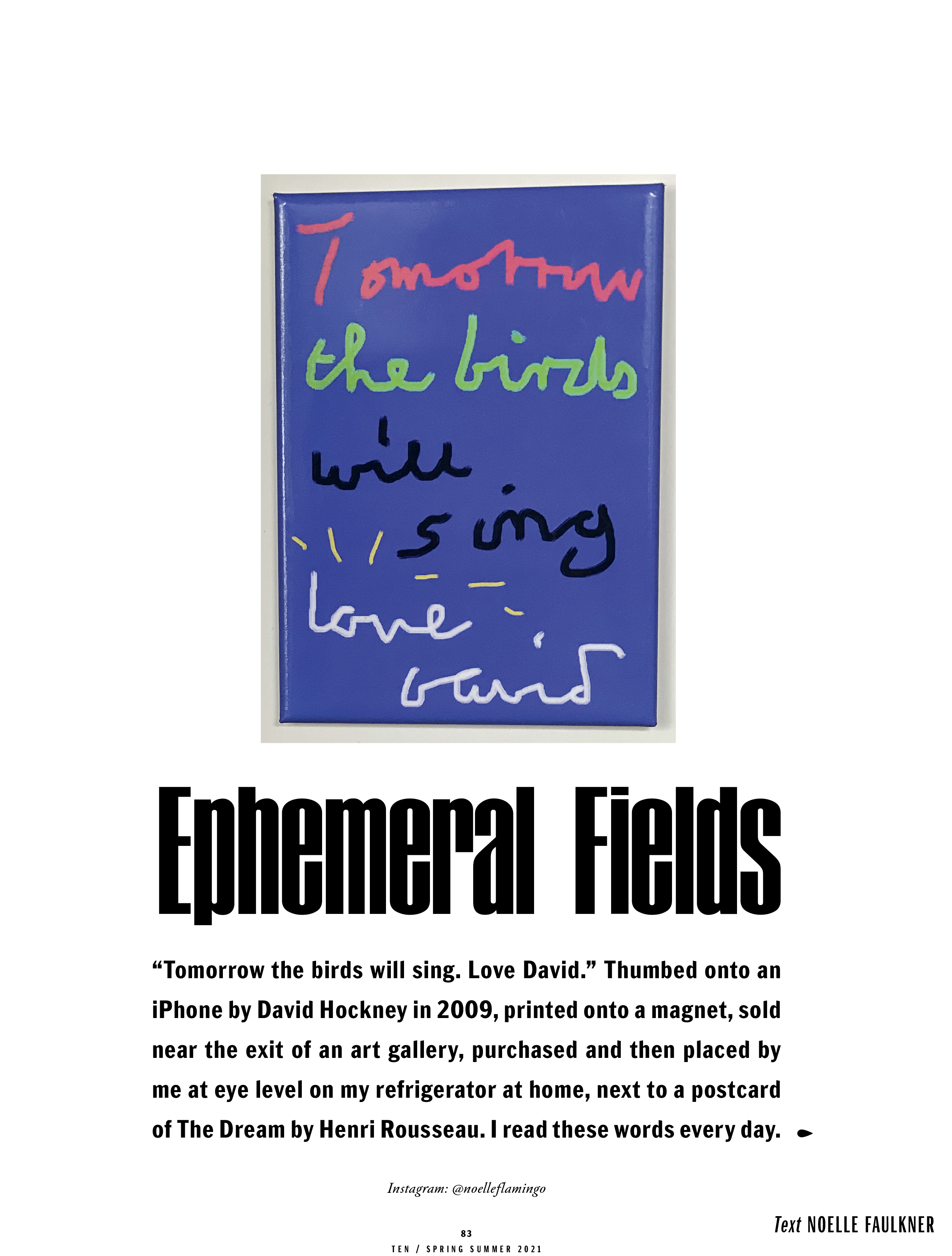

I did not lay eyes on my little purple affirmation for almost a year. The pandemic forced me to (accidentally) spend most of 2020 in the UK’s rural north. During the bleak end of winter, I lived in isolation with my English boyfriend and his family in a small village of stone houses, vast fields and a medieval church. I would walk the bare, brown fields so much, I gave them names. My favourite, exactly 2,461 steps away, was “Rothko field”, named as such for its rich gradient of umber. As doom took hold of the world, the weather behind my eyes changed. I became stormy, uneasy. My screen time surged as I spent hours scrolling for peace, using the only tool for connection I knew: my iPhone. Instead of the digital flowers and positive affirmations I so needed, social media shoved broken stems, rotten foliage and dead air down my throat. Soon, I forgot about the daily schedule of the winged chorale outside, despite a world on pause leaving them louder than ever.

Until, one day, it happened. “A message from David Hockney” flashed on my screen. I tapped a link, and an iPad sketch of daffodils in a field glowed back at me. Nature’s golden trumpets had a proclamation: “Do remember they can’t cancel the spring. Love David.” It wasn’t a personal message, of course. The British artist had sent it to the entire world, a fresh bunch of blooms immortal, from his Normandy home. Love life. Tomorrow the birds will sing. Be brave, face life. I clung to daffodils like I was a duty-free koala, and began looking for them on my walks. Daffodils, then tulips, cherry trees and then peonies gave me a sense of resolve.

My boyfriend had casually pointed out that we weren’t far from East Yorkshire, where Hockney painted his many landscape scenes, including the famous se- ries, The Arrival of Spring (2011). The death of his gallerist friend Jonathan Silver in 1997 first inspired Hockney’s big skies and vivid landscapes of Yorkshire – they are a witness statement of time and mortality. When Silver was in his final stages of cancer, Hockney would drive almost 200km across the Wolds to see him, watching the land shift as the planet moved around the sun. “I started noticing the countryside and how it changed,” he said. “Because it’s agricultural land around here, the surface of the earth itself is con- stantly being altered. The wheat grows, then it’s harvested, then you see it ploughed.”

“During times of crisis, we naturally seek out the familiar,” experts on the radio would offer. I missed my dog. My bed. I missed the smell of Australian natives. Little was familiar to me here. I was like one of those inflatable men you see at used-car yards, flapping about in a windy purgatory, with nothing to hold on to. Art, it turned out, would become my grounding wire, nature, the electricity.

“The world is very, very beautiful if you look at it,” Hockney said in an interview last year. “But most people don’t look very much, do they? They scan the ground in front of them so they can walk, but they don’t really look at things with intensity.” Hockney goes on to tell an anecdote about a philosopher on television who is asked how he can be optimistic when the news is so bad. “He said, ‘That’s television – bad news sells.’ And this [interviewer] said, ‘Well, what’s the good news, then?’ And he said, ‘Well, the arrival of spring,’” Hockney said with a smile. “Yes, it is good news, but nobody notices it. A few people – but at one time everybody will notice it.” After pouring over a decade’s worth of Yorkshire landscapes, it was Hockney’s iPad drawings that captured me – they were painted from a perspective that showed everything at once, like a window. They had movement, energy and depth. I saw Hockney’s sense of adventure in the hedgerows and bridleways; I found his romantic tenderness in the hawthorns and in the “tunnels” of horse chestnut trees that lined the B-roads. I, too, witnessed the landscape change from brown, to green. And I was surprised to find psychedelic seas of colour, fields of purple echium flowers, neon rows of rapeseed or masses of white poppies and the vibrant sunflower fields that were the finale in the summer. I would wander into the darkness at night, tracing the moon as it moved across the sky, lighting up the rows of crops. In an unintentional mirroring act, I even sent photos of flowers and fields back home for friends to wake up to.

Hockney painted on his iPad throughout 2020. His lockdown works (including the daffodils) will be shown this year at the Royal Academy in Lon- don. With the help of hindsight, I wonder how these works will spark new perspectives in others – what did Hockney see differently this time? “Many tell me these drawings offer respite at this testing time,” Hockney wrote in a letter read out on a French radio station last spring. “They are testament to the cycle of life, which begins here with the birth of spring... Idiots that we are, we have lost our link with nature even though we are part of it complete- ly. All of this will end one day. What lessons will we learn? I’m 83, I’m going to die. We die because we are born.”

I used to wonder why the “Tomorrow, the birds... ” work was made into a gift-shop magnet – it is not a famous work by any means. It’s funny how this mass-made souvenir, the size of an old iPhone screen, has shifted closer to its original intention than it would have done had it been hung in a gallery. Its intimacy and sentiment transcended the medium, just like a text message can. Like millions of others, my household experienced death during those months, but the ephemeralness of nature gave us verve. And it was in the surprising influence of Mr Whizz, as the British artist is known, where I found solace and perspective. Besides, what is art if it does not inspire a new way of seeing? “The only things that matter in life are food and love, in that order, and also our little dog Ruby,” Hockney signs off in that pub- lic letter. “I truly believe this, and for me, the basis of art is love. I love life.”

David Hockney: The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020, March 27-August 22; Royal Academy, London W1 (royalacademy.org.uk)