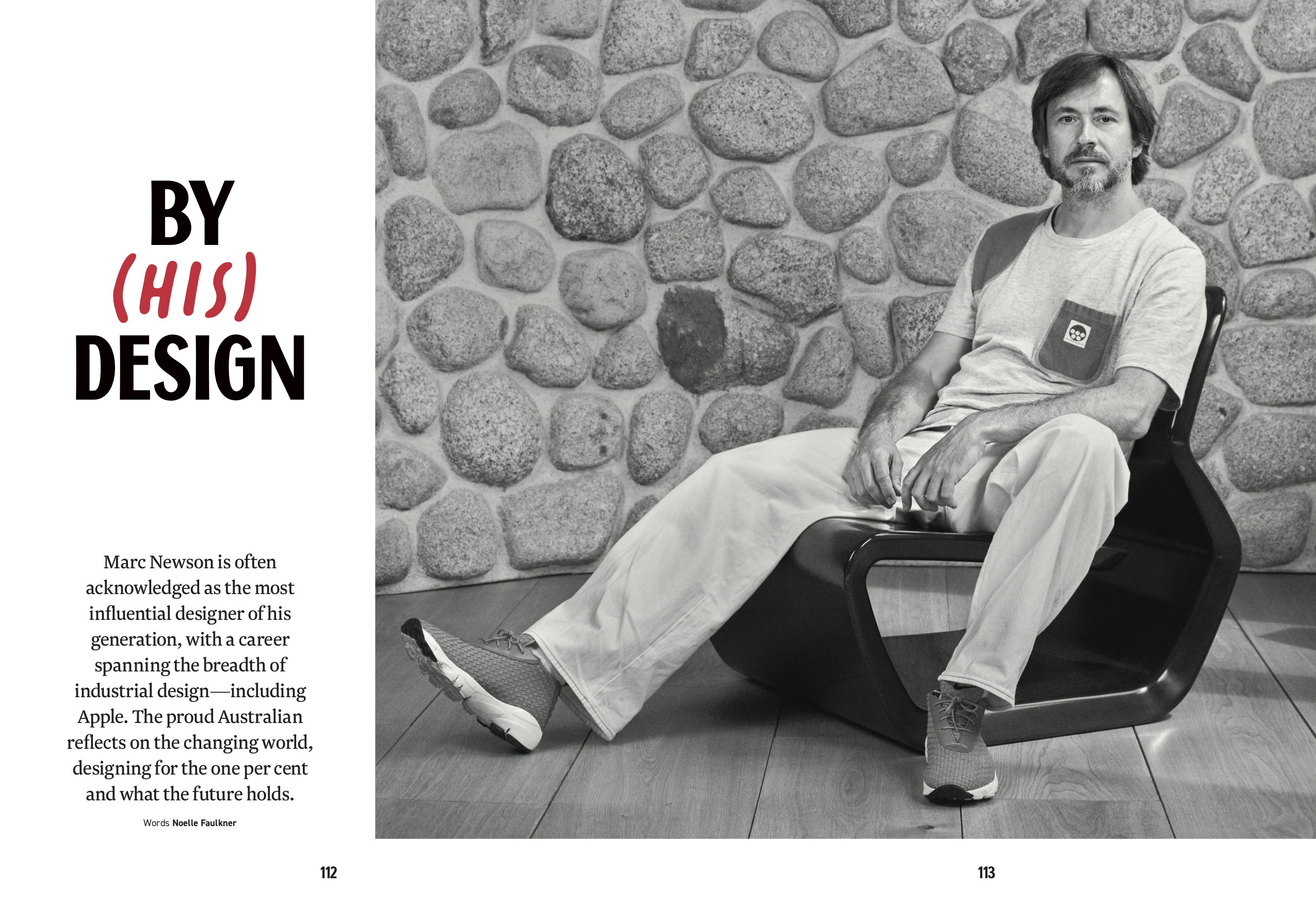

Marc Newson is often acknowledged as the most influential designer of his generation, with a career spanning the breadth of industrial design—including Apple. The proud Australian reflects on the changing world, designing for the one per cent and what the future holds.

Fundamentally, my job is problem-solving. Designing always boils back to the fact you’re solving problems,” says Marc Newson, explaining his role as a designer with fingers in many, many pies. “You’re a gun for hire. A troubleshooter. Why are you doing it otherwise? The reason you do this is you’re either dissatisfied with the way things are or something needs to be improved. So clearly, my job relies on the reality that there is a degree of dissatisfaction and an unworthiness in products out there. If everything was perfect, I’d be out of a job.”

As one of the world’s most influential modern industrial designers, it’s much easier to list what the Sydney-born, UK-based designer’s Midas pen has not touched in his pursuit of perfection. His oeuvre spans furniture, jewellery, luggage, aviation, timepieces, interiors, homewares, marine, footwear, technology and aerospace. His client list includes Louis Vuitton, Hermès, Nike, Hennessy, Dom Pérignon, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Georg Jensen, R.M Williams and Riva; and his CV reads creative director of Qantas and special projects designer for Apple (where he helped design the Apple Watch).

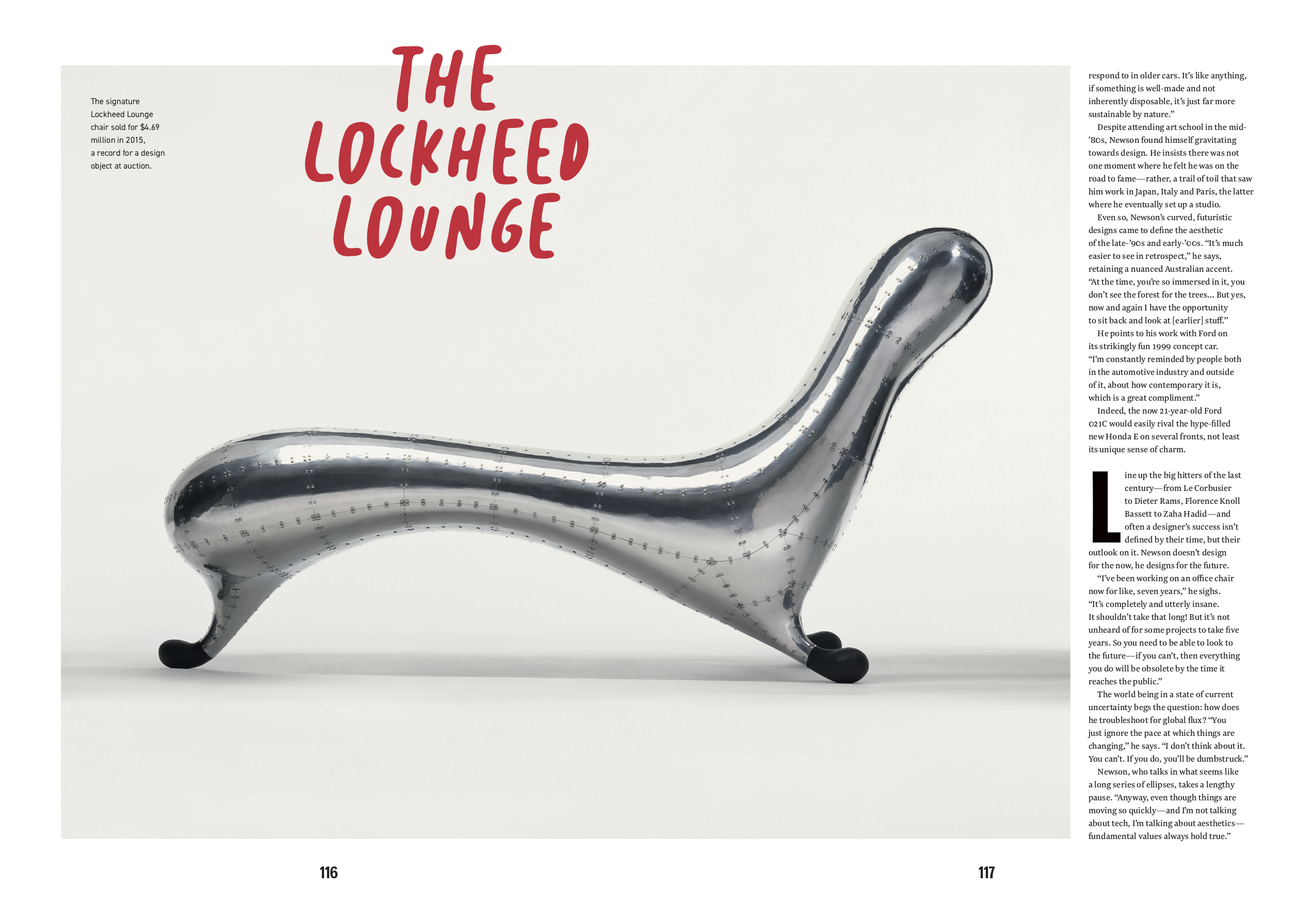

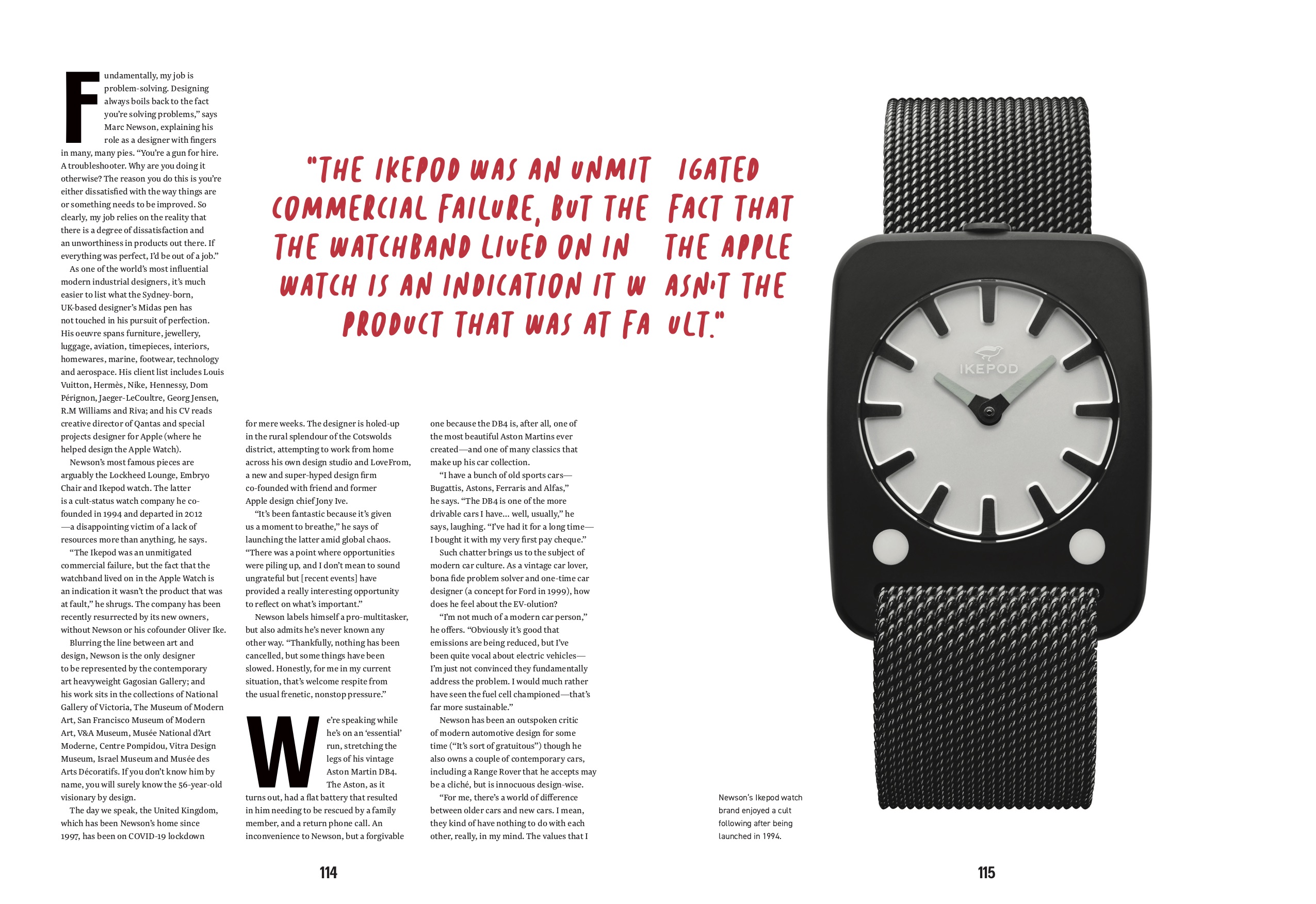

Newson’s most famous pieces are arguably the Lockheed Lounge, Embryo Chair and Ikepod watch. The latter is a cult-status watch company he co- founded in 1994 and departed in 2012 —a disappointing victim of a lack of resources more than anything, he says.

“The Ikepod was an unmitigated commercial failure, but the fact that the watchband lived on in the Apple Watch is an indication it wasn’t the product that was at fault,” he shrugs. The company has been recently resurrected by its new owners, without Newson or his cofounder Oliver Ike. Blurring the line between art and design, Newson is the only designer to be represented by the contemporary art heavyweight Gagosian Gallery; and his work sits in the collections of National Gallery of Victoria, The Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, V&A Museum, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Vitra Design Museum, Israel Museum and Musée des Arts Décoratifs. If you don’t know him by name, you will surely know the 56-year-old visionary by design.

The day we speak, the United Kingdom, which has been Newson’s home since 1997, has been on COVID-19 lockdown for mere weeks. The designer is holed-up in the rural splendour of the Cotswolds district, attempting to work from home across his own design studio and LoveFrom, a new and super-hyped design firm co-founded with friend and former Apple design chief Jony Ive.

“It’s been fantastic because it’s given us a moment to breathe,” he says of launching the latter amid global chaos. “There was a point where opportunities were piling up, and I don’t mean to sound ungrateful but [recent events] have provided a really interesting opportunity to reflect on what’s important.” Newson labels himself a pro-multitasker, but also admits he’s never known any other way. “Thankfully, nothing has been cancelled, but some things have been slowed. Honestly, for me in my current situation, that’s welcome respite from the usual frenetic, nonstop pressure.”

We’re speaking while he’s on an ‘essential’ run, stretching the legs of his vintage Aston Martin DB4. The Aston, as it turns out, had a flat battery that resulted in him needing to be rescued by a family member, and a return phone call. An inconvenience to Newson, but a forgivable one because the DB4 is, after all, one of the most beautiful Aston Martins ever created—and one of many classics that make up his car collection. “I have a bunch of old sports cars— Bugattis, Astons, Ferraris and Alfas,” he says. “The DB4 is one of the more drivable cars I have... well, usually,” he says, laughing. “I’ve had it for a long time— I bought it with my very first pay cheque.”

Such chatter brings us to the subject of modern car culture. As a vintage car lover, bona fide problem solver and one-time car designer (a concept for Ford in 1999), how does he feel about the EV-olution? “I’m not much of a modern car person,” he offers. “Obviously it’s good that emissions are being reduced, but I’ve been quite vocal about electric vehicles— I’m just not convinced they fundamentally address the problem. I would much rather have seen the fuel cell championed—that’s far more sustainable.”

Newson has been an outspoken critic of modern automotive design for some time (“It’s sort of gratuitous”) though he also owns a couple of contemporary cars, including a Range Rover that he accepts may be a cliché, but is innocuous design-wise.

“For me, there’s a world of difference between older cars and new cars. I mean, they kind of have nothing to do with each other, really, in my mind. The values that I respond to in older cars. It’s like anything, if something is well-made and not inherently disposable, it’s just far more sustainable by nature.”

Despite attending art school in the mid- ’80s, Newson found himself gravitating towards design. He insists there was not one moment where he felt he was on the road to fame—rather, a trail of toil that saw him work in Japan, Italy and Paris, the latter where he eventually set up a studio. Even so, Newson’s curved, futuristic designs came to define the aesthetic of the late-’90s and early-’00s. “It’s much easier to see in retrospect,” he says, retaining a nuanced Australian accent. “At the time, you’re so immersed in it, you don’t see the forest for the trees... But yes, now and again I have the opportunity to sit back and look at [earlier] stuff.” He points to his work with Ford on its strikingly fun 1999 concept car. “I’m constantly reminded by people both in the automotive industry and outside of it, about how contemporary it is, which is a great compliment.” Indeed, the now 21-year-old Ford 021C would easily rival the hype-filled new Honda E on several fronts, not least its unique sense of charm.

Line up the big hitters of the last century—from Le Corbusier to Dieter Rams, Florence Knoll Bassett to Zaha Hadid—and often a designer’s success isn’t defined by their time, but their outlook on it. Newson doesn’t design for the now, he designs for the future. “I’ve been working on an office chair now for like, seven years,” he sighs.“It’s completely and utterly insane.

It shouldn’t take that long! But it’s not unheard of for some projects to take five years. So you need to be able to look to the future—if you can’t, then everything you do will be obsolete by the time it reaches the public.”

The world being in a state of current uncertainty begs the question: how does he troubleshoot for global flux? “You

just ignore the pace at which things are changing,” he says. “I don’t think about it. You can’t. If you do, you’ll be dumbstruck.”

Newson, who talks in what seems like a long series of ellipses, takes a lengthy pause. “Anyway, even though things are moving so quickly—and I’m not talking about tech, I’m talking about aesthetics— fundamental values always hold true.”

His formula, he eventually offers, is simple: do things at his own pace, on his terms, sticking to his guns. “You have to be mindful of the world we live in but not get bogged down by it,” he says. The tales of Apple’s inner-utopia have become the stuff of legend, especially among the design and tech communities, and Newson does nothing to shatter the myth. From the beginnings of their partnership at Apple, Newson says he and Ive had a synchronistic way of working—a philosophy that they will carry into LoveFrom (the company’s name itself is a nod to Steve Jobs’ from- the-heart creative ethos). Indeed, a lot of it comes from a common problem-solving attitude, but also, Apple gave its team the freedom to work as such. “With Apple, more than an aesthetic, it was a philosophy,” Newson says of working with the tech giant. “Things are done in a very singular way. Problems and goals are identified early on and constraints don’t become the parameter that dictate the way something is brought to market. If a piece of kit doesn’t exist, they will simply invent it, the production line that goes with it and the economy that surrounds it.”

This is not how most companies work. “Industry generally works in a far more reactive way... It’s a bit like trying to figure out a better way to mend a flat tyre when you’d be better off just rethinking the wheel, so you never had flat tyres.” Right now it’s hard to talk about manufacturing without exploring the notion of sustainability—a term that Newson finds as irritating as “wearable” and, well, “luxury”.

“It’s just become this blanket term that has found its way into our language,” he says. “There are a million aspects to sustainability. Material sustainability, philosophical sustainability and the whole question of obsolescence... I’d like to think that I’m designing things that are not designed for landfill. That’s the worst demonstration of everything bad about our society, in terms of consumption.” He adds: “I think for people like me, for designers to create great things, industry needs to get on board or to evolve in a way like Apple did. Where design and industry have completely, I believe, meshed.”

Granted, Newson’s biggest critics all seem to have the same issue with his work: it’s designed for the one per cent, the privileged. Jet pack prototypes, million- dollar chairs, special edition fountain pens, speedboats—he’s even designed a $38,000 shotgun for Beretta, named the 486 by Marc Newson. But he argues that the elite have a conscious for craftmanship. “Take the role of the Louis Vuitton luggage that I’ve designed. One of the really interesting things, and one of the reasons I respond positively to working with companies like that, is that everything they make is repairable. The alternative would be to design for some company that mass produces things, makes them far more accessible to the general population, but far worse for the environment because they simply can’t be repaired and end up on a rubbish pile.”

Newson recalls a quote from former Hermés CEO Jean-Louis Dumas (‘It’s not expensive, it’s costly; there’s a big difference’) before revealing that two megayachts he recently designed are being built. Newson believes they could end up being among the biggest in the world, at least in terms of tonnage. “It’s easy to poo-poo an oligarch who spends half a billion on a boat,” he offers. “But the reality is, as absurd as that is, it provides livelihoods for many, many thousands of fine craftspeople and enables fine crafts and engineering expertise that would cease to exist otherwise.”

There are many arguments about the role of design, or rather, what defines ‘good design’. For some, it’s form met with equal function; for others, that balance is asymmetrical. In Newson’s case, being art-trained has sometimes meant his works blur the lines. Like his beloved DB4, they’re not always highly functional, but their beauty endures.

Take his famous Lockheed Lounge, which holds the record for the most expensive design object sold at auction (securing $4.69 million in 2015). Newson will readily admit that it’s not the plushest of chairs—but if you’re looking at his work through the same lens as a La-Z-boy, then it’s not for you.“I’m designing sculpture or furniture or whatever you want to call it,” he says of his niche. “You can sit on these things. I don’t discourage people to sit on these things, but they’re not much more comfortable than a bus stop. They have a function, but their primary function is not that. They have a different function.”

Newson is from the school of thought that design, at the very least, should provide choice. “One of the things that I love about design, it’s not like architecture in the sense that it’s imposed upon you,” he says. “If you have to go to a certain building to work every day, and you hate it, there’s not a hell of a lot that you can do about it. Design has a much greater ability—you can either take it or leave it.”