The art scene’s next

frontier? Embracing

tech in all its forms.

Qantas Art and Culture Report, December 2023 (PDF)

Qantas Art and Culture Report, December 2023 (PDF)The art scene’s next frontier? Embracing tech in all its forms.

By Noelle Faulkner, additional text by Bek Day

Nature manufactured

Sam Leach

Sam Leach’s paintings draw on the natural world and often feature animals, landscapes and, thanks to his recent forays into AI, surreal elements or placements in between. Leach (sullivanstrumpf.com), who won the 2010 Archibald and Wynne prizes, has incorporated AI into his practice for about six years and exhibited his first AI-assisted works in 2018 at the Tattersall’s Club Landscape Art Prize in Brisbane, followed by a solo show at Sydney’s Sullivan+Strumpf in 2020. He’d become intrigued by the work of neuroscientist Professor Mandyam (Srini) Srinivasan, who he’d painted a portrait of in 2014. “He was building these drones, which he trained using research on animal behaviour,” says Leach. “I got interested in the visuals he was producing.”

Inspired, the Melbourne-based artist started to explore. “At that time, the first GANs [Generative Adversarial Networks – a deep-learning framework for generative AI] were emerging and able to produce reasonably decipherable images. Someone with extremely limited programming skills, like myself, could get a handle on how to implement it. That’s what kicked it off.

“I’d seen early programs trying to replicate hand-drawn numbers I so wanted to see if it could produce a version of my paintings.” The breakthrough moment came when the programs not only started producing images that were recognisably informed by elements of his work – animals, trees and other figures – but offering up concepts he had never considered. “I have a dataset of my paintings that I give to the algorithm. It learns the patterns and tries to produce a new work that would fit in.”

There are three parts to the algorithm: “The first produces images, the second asks, ‘Is this a real painting Sam has produced?’ and decides. Then the two parts learn from each other. One is trying harder to produce a work that will fool ‘the critic’ part and the critic is getting better at determining which are real or fake.” After thousands of cycles, Leach started getting new images that he acknowledged could have been painted by him. “In the past, I’ve painted a lot of birds and the algorithm picks up on that and might produce hybrid birds or a bird that looks like it’s exploded into a tree. It keeps it interesting and surprising.”

While the output is small-scale, resulting from code Leach programs himself, he attempts to reproduce the pixelated thumbnail created by the AI, painting new original artworks. “There’s a lot of reinterpretation that I do to shape it into a recognisable image. The algorithm does the cognitive labour, which frees me up to be more experimental in my painting.”

Muse in the machine

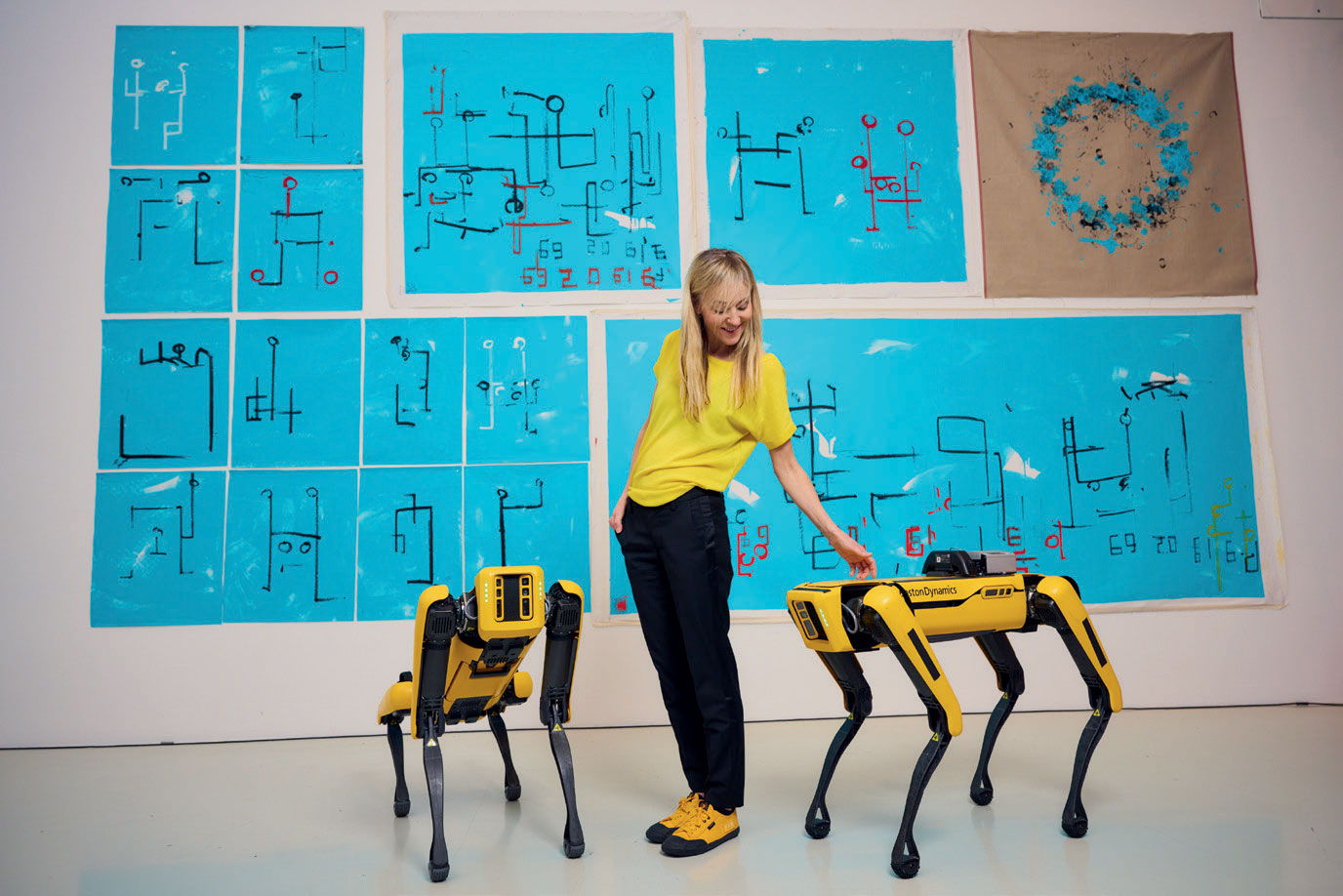

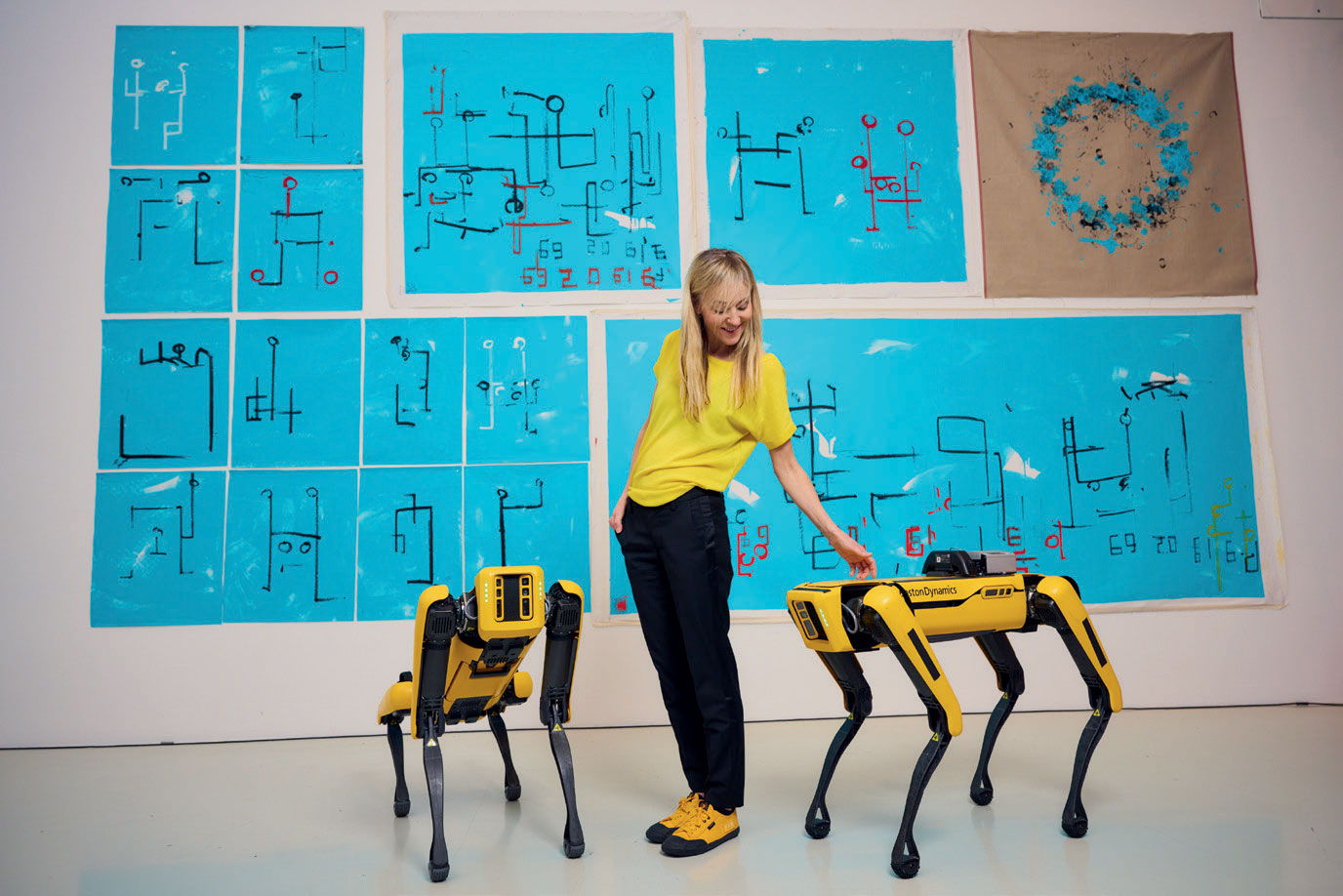

Agnieszka Pilat

Working at the intersection of robotics, AI and fine art, Polish-born, American-based painter Agnieszka Pilat believes that robots are the celebrities of the future. Not only does she incorporate their images in her portraiture work – not unlike noblemen and women of the Renaissance – but she also trains the machines themselves to create art.

“Historically, portraiture has always reflected power in society,” says Pilat. “Right now we’re in an interesting moment in history, which I think is hyper-narcissistic. Selfies are the number-one portrait. So as a portrait artist, I ask, ‘What is the new aristocracy?’” To Pilat, the answer is clear: the machine.

At first, she began painting older, derelict machines but a visit to robotics company Boston Dynamics led her to paint a portrait of Spot, the company’s robotic canine. “I thought of Spot as the celebrity machine, kind of like a Marilyn Monroe of robotics. That’s what Andy Warhol would do.”

Pilat has been an artist-in- residence at SpaceX in California and Boston Dynamics. Her work can be found in the personal collections of many Silicon Valley bigwigs and was even used to decorate the sets of The Matrix Resurrections. And from this month at the National Gallery of Victoria’s Triennial, visitors will be able to witness three of Pilat’s Spot robots painting live.

Pilat refers to the exhibition environment as a nursery or classroom, where the Spot robots, pre-programmed with 16 symbols, operate autonomously and progress in their work and practice over time. “These machines are awkward and so the drawings are very silly,” she says. “They’re like children.” Pilat enjoys the paradox of artistic robots – where the expectation might be that they create perfect, repetitive mass-produced works, the outcome is the opposite.

“The thing about robots is that, yes, all they do is driven by AI but it’s always a hybrid of machine learning and programming.” For example, when Spot is walking up the steps,

it uses AI to navigate but it combines that with pre-loaded data for navigating stairs. “In that sense, it’s a similar learning curve as children – some of what humans learn is hardwired and some is learned by experience. Robot art-making follows a similar path.”

The “ghost in the machine”, says Pilat, is when the robot makes mistakes 135 and we can’t trace the source. “That’s where art comes to life.”

Back to the future

Anna Pogossova

Photographer and sculptor Anna Pogossova (annapogossova. com) is inspired by what she refers to as “culturally handed down imagery” – cultural and historical references that she collects and uses to reconstruct fantastical still-life images of objects, combining set-building and design techniques with sculpture and fine-art photography.

The Sydney-based artist has created arresting pop-surreal imagery for magazines such as Vogue and brands including R.M. Williams, Mecca Cosmetica, Country Road, Sephora, Adobe and David Jones, while also exhibiting her work at Sydney gallery Jerico Contemporary and the city’s Powerhouse Museum, plus at last year’s Melbourne Design Week.

“I will choose two disparate kinds of iconographies – things I might pick up, advertisements, films, references in pop culture, symbols or historical art – things that shouldn’t go together but kind of do. And I wonder why that is.” Through the merging of these reference points, Pogossova ponders

the “invisible library of things” that exists within the human subconscious and how we draw upon our memory of images. It was this thought exercise that led her to start experimenting with AI programs. “I felt like AI was doing something similar.”

Following a period of experimentation, first with DALL-E and then Midjourney, Pogossova found the AI programs started to open up new possibilities that would not only streamline her process but crystallise her thoughts and creative ideas. “I started inputting my works – a sculptural work with a photographic element, a photographic work and maybe a reference that I’d manually collected, let’s say, from a science fiction film – and had [the AI] generate some ideas,” she says. “The result unlocked something I always wanted: a method of visualising what was in my mind.”

Pogossova found she could reverse-engineer a physical work that she had been thinking about but didn’t have the time or means to experiment with, which, as an emerging artist, proved invaluable. “Normally, it would take me weeks to mock up, realise and experiment with an idea in the studio but what the AI gives me is like a sketch or a study of what my brain is thinking. It’s a dream machine.”

Songs of tomorrow

Justin Shave and Charlton Hill

Heading up a team of producers, composers, data scientists and sonic technologists, Justin Shave (above left) and Charlton Hill (right) of Uncanny Valley (uncannyvalley.com.au) make music for some of the world’s biggest names. In 2020, their technology-led production studio based in Sydney won the first Eurovision-inspired AI Song Contest music prize. Most recently the team produced Music of the Sails, a sonic livestream celebrating the Sydney Opera House’s 50th anniversary with music composed by machine learning via data generated by the building’s operations.

“Musicians have been using software and computer systems for as long as we can remember,” says Hill. “It’s just that the tools of the trade have increased in their intelligence and their assistance. AI is somewhat of a natural progression and the way we’ve seen the industry evolve. Good music will always have that human element so for us, it’s just creativity on steroids.”

Hill and Shave are constantly looking for new ways to incorporate machine learning and AI technology into their practice, with artist development always at the centre. In 2019, they collaborated with Google’s Creative Lab and emerging Australian artists on a project that used machine learning to create new songwriting tools. “We found that every artist was using the technology in different ways so it wasn’t a one-size-fits-all tool,” says Shave.

Today, the studio is focused on finding fresh ways to work with the tech, including new software experimentations that can democratise the production process for many artists and help them develop and visualise their ideas or facilitate happy accidents in the studio. Take their MEMU, for example – a complex AI-powered engine that can offer real-time remixing and mash-ups using the artist’s own work, which has the potential to create new sounds and new revenue streams for artists. MEMU tracks the micro-contributions of each artist in each track, and how they are used, which can ensure artists are credited and remunerated.

“Right now, there is not as much diversity in pop music, in terms of the nature of songs, chord progressions etcetera, as there should be,” says Hill. “So here comes technology to shake things up a bit. We welcome it for that reason, because if the art is turned around and suddenly we’re hearing sounds that we’ve never heard before... what an incredibly creative time to be alive.”