The lost girls: Women with ADHD have missed red flags that haunt us.

After multiple burnouts and chronic overwhelm, in my early 30s I finally knew why life sometimes felt harder for me. It made perfect sense, so why had no one noticed before?

The Guardian, November 2020 (link)

Are your goals too high? When you explained your job to me…” the psychologist trailed off. I knew where this was going. I was here after six visits to the GP in two years, all for unexplained exhaustion. Burnout, I guessed. Whatever that means.

It felt like my brain had been tossed into a washing machine, and all of the delicate bits that made it sparkle had dissolved. Everything took three times longer than it should have. Somehow, over the past few years, my already-frayed cognitive controls had just … evaporated. “I can’t keep it up any more,” I said wearily. “It” being life. I wasn’t suicidal; I was chronically overwhelmed.

The psychologist tightened her lips. “You know many women in your industry put pressure on themselves to be perfect.”

My eyes began to sting. I had a lot on, but it wasn’t anything someone with my experience shouldn’t be able to handle – I just needed someone to show me how. “There are women out there my age running the world! All I’m trying to do is send a few emails, keep my house clean, be creative and still have free time! I’m not curing cancer or raising a family. I am just trying to live.” I’d always been chaotic, but this was a new level.

The session, I can say with full confidence, was a failure. I left the psychologist’s office with zero helpful tools and as much hope. I had known depression. This wasn’t it. Stress? Anxiety? Sure. But these were byproducts, not the cause. What is wrong with me? As soon as I got home, I collapsed on to the floor and tucked my limbs under myself into a ball – which I did often. How does everyone else cope with life?

It would be another burnout, two more doctors, a blood test, a hormone test, a three-month wait to see a psychiatrist and another year-and-a-half before I had an answer. It turned out, like many women in their 30s, I had been masking severe ADHD my entire life. And like so many more, I had no clue what that meant.

Attention deficit hyperactive disorder is a condition that presents at first in childhood but often goes undiagnosed. In Australia, it affects approximately 814,500 people and around five to 7.1% of the population globally. Despite the name, ADHD doesn’t exactly result in a “deficit” of attention, but more an issue regulating it, making it harder to plan, prioritise, avoid impulses, remember things and focus.

On a good day, it’s like watching a train whizz past you while you’re trying to read the text on the side and make out faces in the windows. On a bad, a bird might land in front of you. Curious, you pull out your phone, Google the bird and get stuck in a “pigeons of the world” vortex. You discover cassowary eggs are bright green and in 2005, UK police found a leg of swan in the Queen’s Master of Music’s freezer. Two terrine recipes later, the train has long passed and night has fallen. Dazed, you sink under a dark cloud of self-loathing, lamenting another lost day. You don’t remember what kind of bird it was.

The default assumption about ADHD is that it’s what makes little boys disruptive. But it can also make little girls feel like they’ll never be good enough. Statistics have traditionally shown ADHD is more prevalent in males, but recent research suggests this could, in part, be due to misdiagnosis. Unsurprisingly, ADHD in women is hugely under-researched – females weren’t even adequately included in findings until the late 90s. And it wasn’t until 2002 that we got our own long-term study.

ADHD presents differently in girls and boys too. Women are more likely to have inattentive ADHD, rather than the more observable impulsive type. Because of society’s gender norms, girls with ADHD are often dismissed as “daydreamers” and “overly sensitive”, as if we are a romantic, quirky caricature from a John Green novel or the Disney Princess canon.

The frequency of zone-outs, disassociations and meltdowns caused by our hidden internal restlessness and our brain’s inability to regulate information and emotion goes unnoticed. The cherry on top is that girls who do suffer from impulsivity are often palmed off as “tomboys”. As a child who was prone to inattentiveness and impulsivity, I was repeatedly told to “stop daydreaming”, “slow down”, “hurry up” and “act like a lady.” Overwhelmed by the world, it wouldn’t take much for my cup to runneth over or for me to completely disassociate – I got very good at both.

There are many women like me: “lost girls”, so we’ve been called. Chaotic and curious, sometimes we feel like superheroes; other times, super-failures. It’s not always a lack of interest that makes it hard for us to process information, but our brain’s desire to absorb so much of it. We are jacks of many trades, purveyors of information, collectors of hobbies, beginners of tasks and finishers of few. And we all have similar stories of missed red flags that haunt us.

When I was nine, my teacher told my parents I was all over the place. I already had the energy for five dance classes a week, netball, French lessons, piano lessons, a book club and school band. However, she thought I still didn’t have enough channels for my “creativity” and suggested they enrol me in drama school as well, so they did. Did it help me focus? Of course not.

Neurodivergent women often slip through the cracks of diagnosis because they can appear smart or gifted. This is because we’re more likely to be perfectionists or suffer from low self-esteem, so we work extra hard to prove ourselves (see also: my burnout). Combined with hyperfocus – the flipside of the attention coin where one zones in on a single interest for hours – this results in flashes of brilliance.

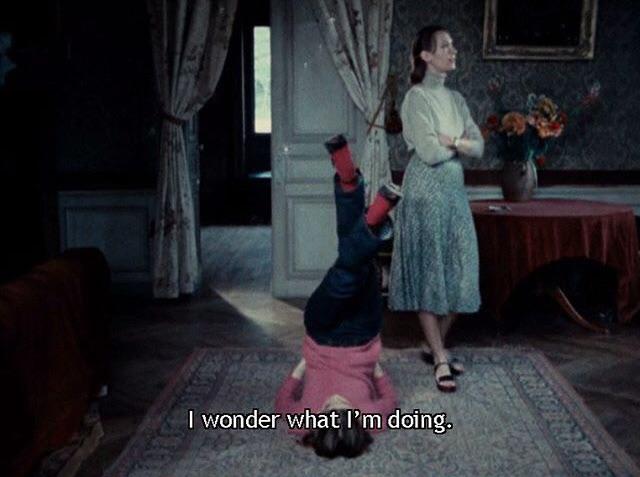

We’re also experts at masking symptoms. We form habits by mirroring the social behaviours of those around us. You think imposter syndrome sucks? Try keeping it together when your brain is a wind-up puppy doing backflips while singing the chorus of Ricky Martin’s The Cup of Life – for no apparent reason. And don’t ask what the obstacles involved in dating or starting new relationships might be!

As I discovered, burnout is what happens when the mask slips. Your entire world comes crashing down, and you don’t have the executive function to figure out which way is up. ADHD adults take an extra 16 days of absence a year, according to a report by the Australian ADHD Professionals Association, so while it certainly makes life interesting, it is a rollercoaster for your REM sleep patterns.

According to the Under the Radar Report, released 25 October by ADHD Australia, there is a lack of education and understanding around the condition. The pandemic has caused ADHD children to feel swamped by the struggles of at-home learning, and adults like me are burning out. Anxiety in those with ADHD is skyrocketing, with 52.4% of children and 64.7% of adults reporting an increase. Keep in mind, neurodivergent conditions often co-present with other mental health disorders, so the scales are already tipped. “It’s been a living hell with no escape or support, I’m mentally exhausted,” a parent of an ADHD child is quoted as saying in the report.

Alas, if there ever was a time where neurotypical people could relate to the anguish of fuzzy focus, it’s now. That absence of motivation and productivity you’re feeling from stress? It’s not far off. The chaos of the pandemic has activated everyone’s fight or flight response and time-blindness.

The new normal sees us assaulted by a relentlessness stream of backlit information stained with emotion and outrage. Anxiety is high. Stunned by stimulation, suddenly it’s harder than ever to silence the background noise. Blend all this with the pressures of attempting to work at a regular pace in an irregular environment, without allowing room for adjustment, and you’ve almost got an ADHD tasting plate.

Seven months on, my diagnosis has become something of a bereavement – I’ve cycled through many stages of grief. I am comfortable with my chaos and relieved I now have answers and an arsenal of tools to prevent me from falling into a hole again. But I keep thinking about all the other lost girls out there. I find myself angry and sad, mourning on behalf of my younger self.

I mourn the unnecessary pressure and all the times the world was too loud, bright or grotesque. I mourn the things she forgot, the skills she could have learned and the relationships her impulsivity, perceived detachment and unhealthy coping mechanisms sabotaged. But most of all, I mourn time lost. Because even though my neurodiversity has sometimes made me the loudest person in a room, because I was a woman, nobody noticed.

• If you or someone you know is struggling with ADHD, ADHD Australia has a list of support groups around the country.

• In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In the UK, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123. Other international suicide helplines can be found at befrienders.org